By the time Europe began to contemplate a new generation of large pressurised water reactors, its nuclear industry was shaped by long experience, diverging national politics, and incompatible regulatory cultures. Within the Franco-German partnership of Framatome-Siemens, an intuition gradually took hold that extreme conservatism in safety design could bridge those differences. If a reactor exceeded the most demanding requirements of any national regulator, the reasoning went, it should be licensable and buildable across a wide range of jurisdictions. The European Pressurised Reactor emerged as an ambitious effort to encode that thesis directly into hardware.

By the late 1980s, Europe appeared well positioned to do so. France had completed a rapid and disciplined national pressurised water reactor buildout. Germany had demonstrated its ability to execute conservative, highly redundant plants through the Konvoi series. Political conditions were shifting as the Cold War wound down, cross border industrial cooperation was gaining momentum, and there was confidence that Europe could converge on a single flagship design that would move smoothly through national licensing regimes from Finland to the United Kingdom.

The EPR was conceived as that design. It sought to combine the scale, fuel efficiency, and digital instrumentation and control heritage of the French N4 lineage with the German emphasis on redundancy, physical separation, and operability and threw in a core catcher to boot. The ambition was to deliver a reactor that reassured regulators through conservatism, silenced critics through margin, and achieved compelling economics through sheer size.

What ultimately emerged was, at 1650MW, the world’s highest output commercial power reactor, and with it a revealing case study in the limits of engineering driven convergence.

Design by Accumulation

At a high level, the EPR remains a familiar large light water reactor. Its core geometry, fuel, and reliance on active safety systems place it squarely within the classical pressurized water reactor tradition. The distinction lies less in conceptual novelty than in the cumulative effect of design decisions layered atop one another.

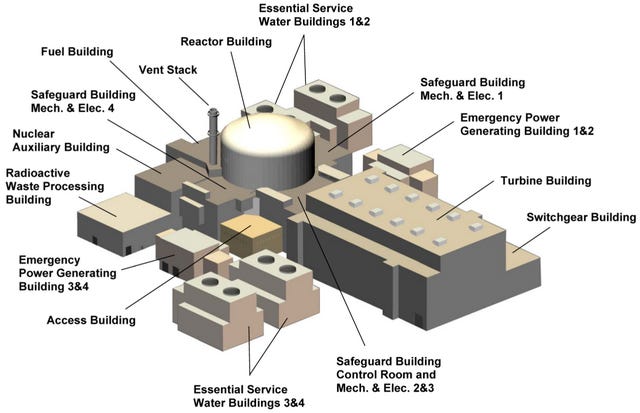

From the French side, the inheritance is clear. The EPR descends directly from the N4 series, a four loop reactor optimized for economies of scale and built around an early, fully digital instrumentation and control architecture. Its core is physically large, with lower average power density, allowing thermal margins and improved fuel utilization to be achieved primarily through geometry and neutron economy rather than by elevating operating limits.

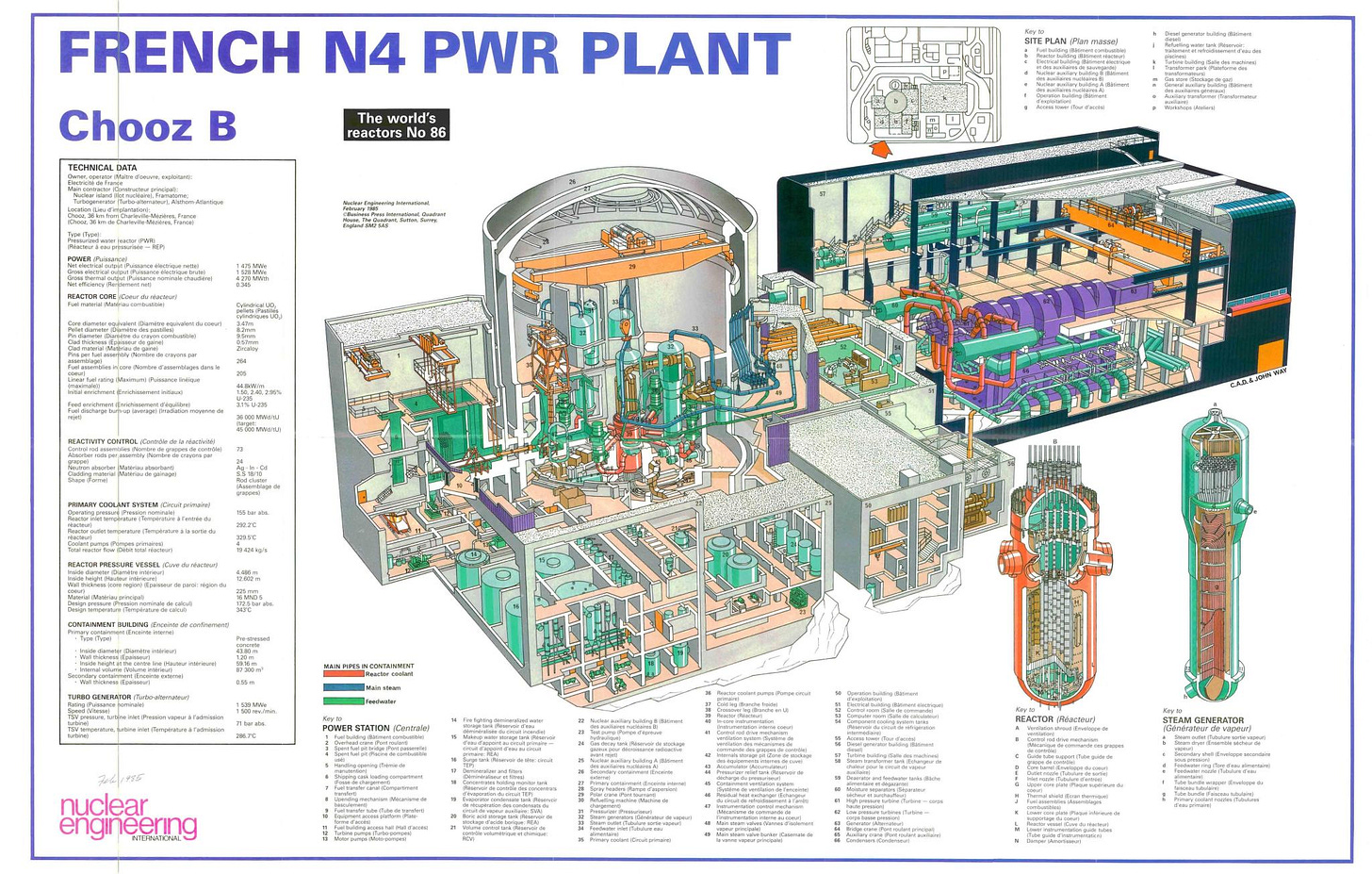

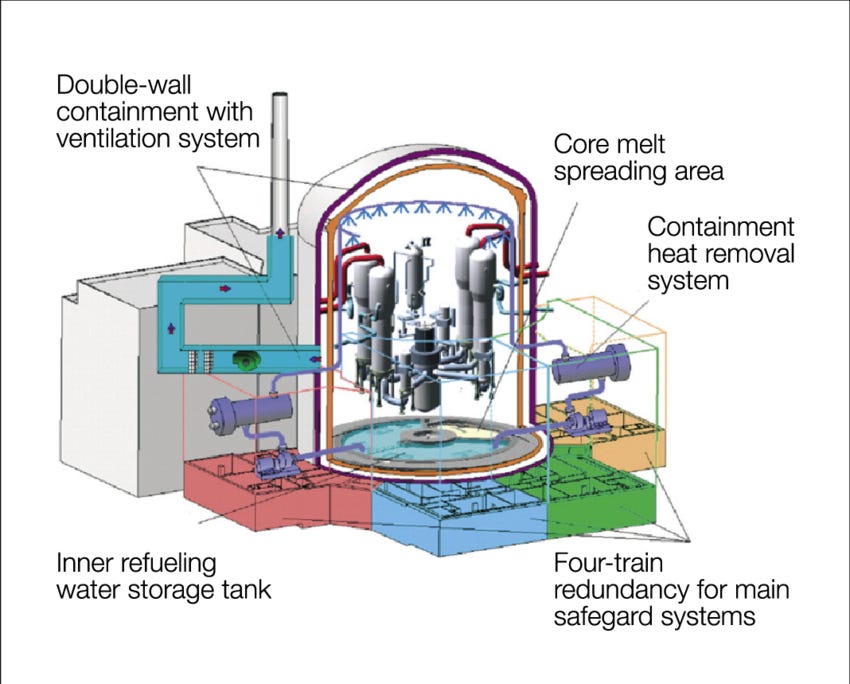

From the German side comes a different emphasis. The Konvoi plants were designed under intense public scrutiny, and the response was to prioritize robustness, separation, and operability. Four independent safety trains, conservative assumptions for external hazards, and generous spatial allowances inside a double containment supported both maintainability and operational flexibility. Space was treated as a safety feature rather than a cost to be minimized.

A safety train, in this context, is not a single system but a complete, independent pathway capable of performing required safety functions on its own. Each train includes its own mechanical systems such as emergency core cooling pumps, piping, valves, and heat exchangers, its own safety classified electrical supply beginning with an emergency diesel generator and dedicated buses, and its own instrumentation and control channel with separate sensors, logic, and actuation paths. All of this equipment is physically separated, seismically qualified, environmentally hardened, and supported by dedicated rooms, cabling routes, penetrations, ventilation, and fire protection so that a failure, fire, or flood affecting one train cannot disable another.

The EPR incorporated both traditions and then extended them. The safety architecture evolved from the partially sized trains of the Konvoi into a configuration where each train was independently 100% capable of meeting the full safety requirements of the reactor. Each train was paired with its own safety related diesel generator, and additional generators were added to support extended station blackout coping. The result was a single unit equipped with six on site safety diesel generators. For reference most PWRs have two.

Each of these decisions was defensible in isolation. Taken together, they produced a plant in which redundancy propagated through every layer of the physical layout. Additional trains required additional compartments, penetrations, supports, barriers, inspections, and procedures.

When drawings meet concrete

The EPR passed its safety case on paper. Its difficulties emerged at the interface between design maturity and construction sequencing, the point at which large nuclear projects typically succeed or unravel.

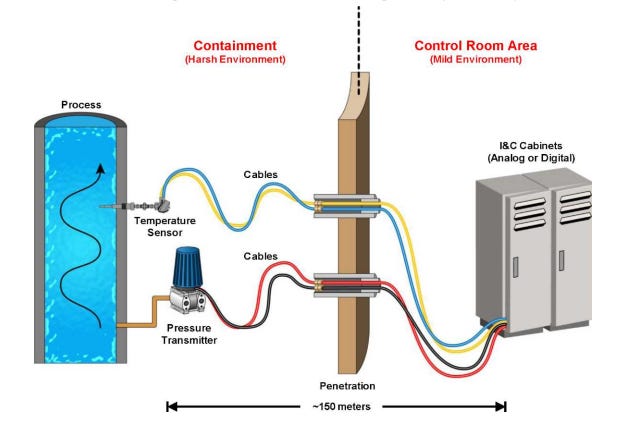

Nuclear plants rarely reach full construction level design completeness before site work begins. Licensing review, vendor final data, and site specific engineering typically proceed in parallel with early civil execution. In first of a kind projects, this sequencing pushes many detailed routing, penetration, and interface decisions late into the build, once physical constraints are already fixed.

The Finnish experience illustrated this dynamic clearly. Regulatory concerns regarding the independence and clarity of the instrumentation and control architecture were resolved only after major structural elements had already been finalized. Addressing those concerns required changes to cabling and system routing that interacted directly with completed safety classified civil works. Each new or modified cable demanded a defined route, typically requiring additional penetrations through structures intended to preserve separation between redundant safety trains. Those penetrations then had to be requalified for fire, flooding, seismic loads, and environmental conditions, triggering repeated inspections, documentation updates, and intrusive modification of concrete that had already been poured, reinforced, and accepted.

The EPR magnified this problem because its redundancy architecture imposed physical separation and seismic qualification across nearly all safety related systems. As a result, civil works, cable routing, fire separation, and seismic supports moved from background engineering considerations into the center of the critical path.

Why similar ideas succeeded elsewhere

The EPR experience does not indict redundancy of active safety trains as a principle. German Konvoi plants embodied many of the same instincts regarding separation, space, and conservatism, and they were delivered successfully. The difference lay in context. Konvoi emerged in an ecosystem with an active supply chain, experienced contractors, and intact institutional memory.

The Korean APR1400 offers a complementary example. It remains an active safety design, but one shaped by selective simplification. Design choices such as direct vessel injection and modified accumulator behavior reduced system count without abandoning the underlying architecture. These were incremental refinements layered onto a familiar and repeatedly executed design.

At Barakah, success followed from continuity in execution. Korea transferred an integrated delivery capability that included engineers, construction managers, suppliers, and established routines. In parallel, the United Arab Emirates invested deliberately in importing expertise from around the world and developing its own cadre of engineers, operators, and regulators.

Redundancy carries a construction sequencing burden, a quality assurance load, and long term maintenance overhead. Organizations that retain the capability to manage those burdens can deliver highly resilient plants. Where that capability has eroded, the cumulative cost compounds across schedule, rework, and reliability.

Simplification as an alternative path

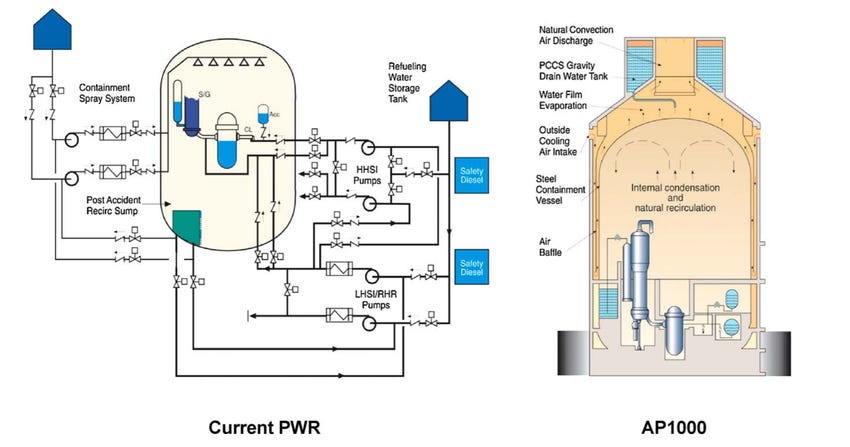

The divergence between the AP1000 and the EPR reflects different institutional pressures rather than different safety ambitions. In the United States, the late Gen 2 buildout left utilities with durable memories of cost escalation, construction disruption, and regulatory churn. By the 1990s, the central concern was no longer extracting additional theoretical safety margin, but restoring economic viability under deregulated markets and constrained utility balance sheets. That experience pushed designers and owners toward simplification and passive safety as a tool to lower OPEX.

This instinct was reinforced by Three Mile Island, which demonstrated that extensive active redundancy did not prevent a serious accident driven by system interaction, operator confusion, and loss of situational clarity. The lesson absorbed by utilities and regulators was that adding systems did not automatically translate into safer outcomes, and that complexity itself could become a risk factor.

The AP1000’s passive safety philosophy emerged from this environment. Westinghouse and its utility customers pursued designs that reduced reliance on active systems and operator action, while the Nuclear Regulatory Commission proved willing to analyze, license, and defend safety cases based on natural circulation, gravity driven injection, and extended grace periods. The regulatory system adapted to accommodate a different expression of safety, one grounded in system elimination rather than system multiplication.

In Europe, institutional pressure moved in the opposite direction. Political reaction to Chernobyl and sustained public anxiety around nuclear risk shaped regulatory expectations toward visible conservatism. Designers responded by layering additional redundancy, separation, and engineered protection onto already conservative pressurised water reactor architectures. The EPR expresses safety through accumulation, aiming to demonstrate exhaustive control over accident scenarios, while transferring much of the resulting burden onto construction sequencing, system density, and physical separation.

Early AP1000 projects showed that simplification does not eliminate first of a kind risk, but it does alter where that risk concentrates. Subsequent nth of a kind builds in China demonstrated that, once design and execution stabilized, the reduced system count supported repeatable construction and predictable delivery. By limiting redundancy and congestion, simplification constrained the surface area over which late design resolution could propagate. The EPR followed a different trajectory, extending active redundancy until the cumulative burden of construction, integration, and qualification became a defining constraint on delivery.

The Retreat from Export Ambition to Domestic Retrenchment and the EPR2

Seen in the order they entered construction, the EPR record ultimately retreated from the ambition that created it.

In Finland, the Olkiluoto plant began construction in 2005 and did not connect to the grid until 2022, a failure of schedule control under a fixed price turnkey contract that transferred design maturity and integration risk onto the vendor and became financially ruinous for Areva, whose reactor business was later restructured and absorbed into Framatome.

In France, Flamanville started in 2007, repeated many of the same execution problems even in the home regulatory environment, reaching full power only in December 2025.

In the UK, Hinkley Point C, launched in 2016 and now expected to enter service only in the early 2030s, reinforces the European pattern. Beyond construction complexity, the UK regulatory process imposed late, highly specific requirements that carried substantial civil and systems penalties, including mandated cooling water intake and fish protection systems that drove additional structures, interfaces, and bespoke engineering into an already congested plant.

The outlier remains Taishan, where construction began in 2009 and the first unit reached the grid in 2018. Even there, delivery was slow relative to the median build times of contemporary Chinese nuclear projects. That gap suggests that execution capability alone was insufficient to fully offset the inherent construction burden of the EPR itself. The fact that China has since moved on to other reactor designs, abandoning the EPR reinforces the conclusion that the architecture proved harder to construct and integrate than alternatives even with high cadence construction programs.

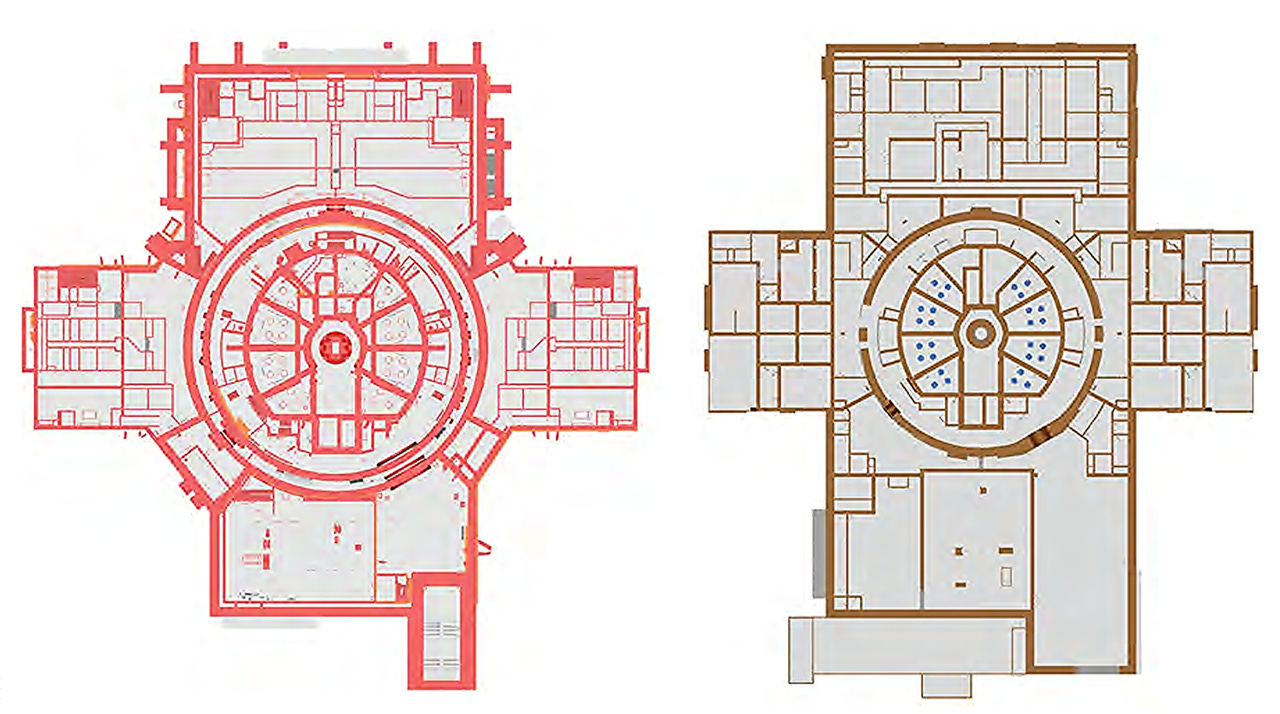

EPR2 is the institutional response to that history. Relative to the original EPR’s four fully capable safety trains, EPR2 reduces the architecture to three safety trains, with simplified separation and a smaller safety classified footprint. The double containment concept is abandoned in favor of a simplified single containment arrangement, reducing concrete volume, penetrations, seismic interfaces, and internal congestion. System layouts and digital instrumentation and control are rationalized around repeatable construction sequences rather than maximal separation.

In the end the export ambitions based on regulatory universality through redundant active safety systems have been explicitly abandoned with the EPR having been effectively withdrawn from international bids. The program is now framed almost entirely around repeat domestic builds in France. The hope is that a single regulatory regime, stable supply chains, and workforce continuity can create lift off for the EPR-2.

We wish them bonne chance!