By Chris Keefer | Decouple Media | February 2026

Recent conversations about the budding nuclear renaissance often begin with the same list. Microsoft restarting Three Mile Island, tech companies partnering with advanced nuclear reactor vendors or the proposed Japanese funded US AP1000 fleet build. These announcements generate headlines, volatile valuations and investor decks.

Meanwhile, forty Westinghouse pressurized water reactors (PWR) sit at roughly the same thermal power output they were commissioned at decades ago, operating within design margins calculated on transistorized computers before integrated circuits existed. Together, these plants hold between 6-10GW of additional capacity, the equivalent of eighteen to thirty 300MW SMRs, that could be unlocked faster and cheaper than any other nuclear source and perhaps even faster than new gas.

My conversation with returning guests Robb Stewart and James Krellenstein, CTO and CEO of Alva Energy, made the case that power uprates at existing PWR plants represent the lowest-hanging fruit in the sector, bypassing the megaproject risks and nuclear supply chain rebuilding that make new nuclear construction so daunting for utilities.

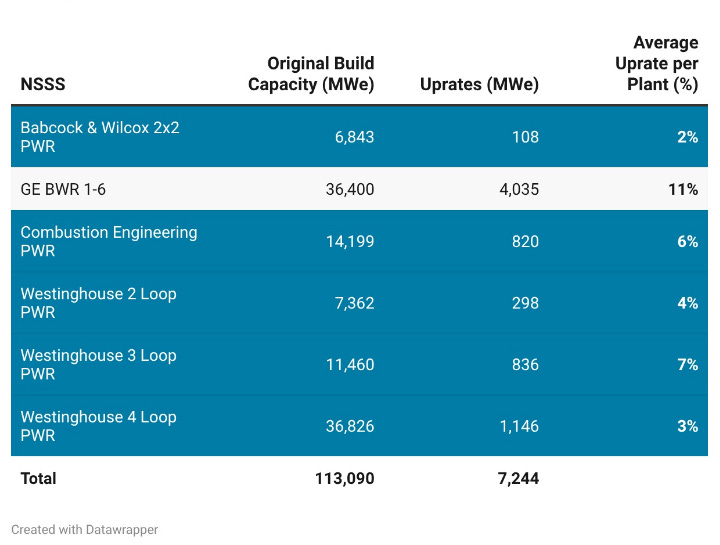

The components turn out to be far more manageable and anticlimactic than new build nuclear: non-safety-related secondary side equipment such as feedwater heaters and condenser tube bundles, alongside nuclear-grade steam generators that the fleet has already learned to replace during their month long scheduled outages using well-rehearsed industrial choreography.

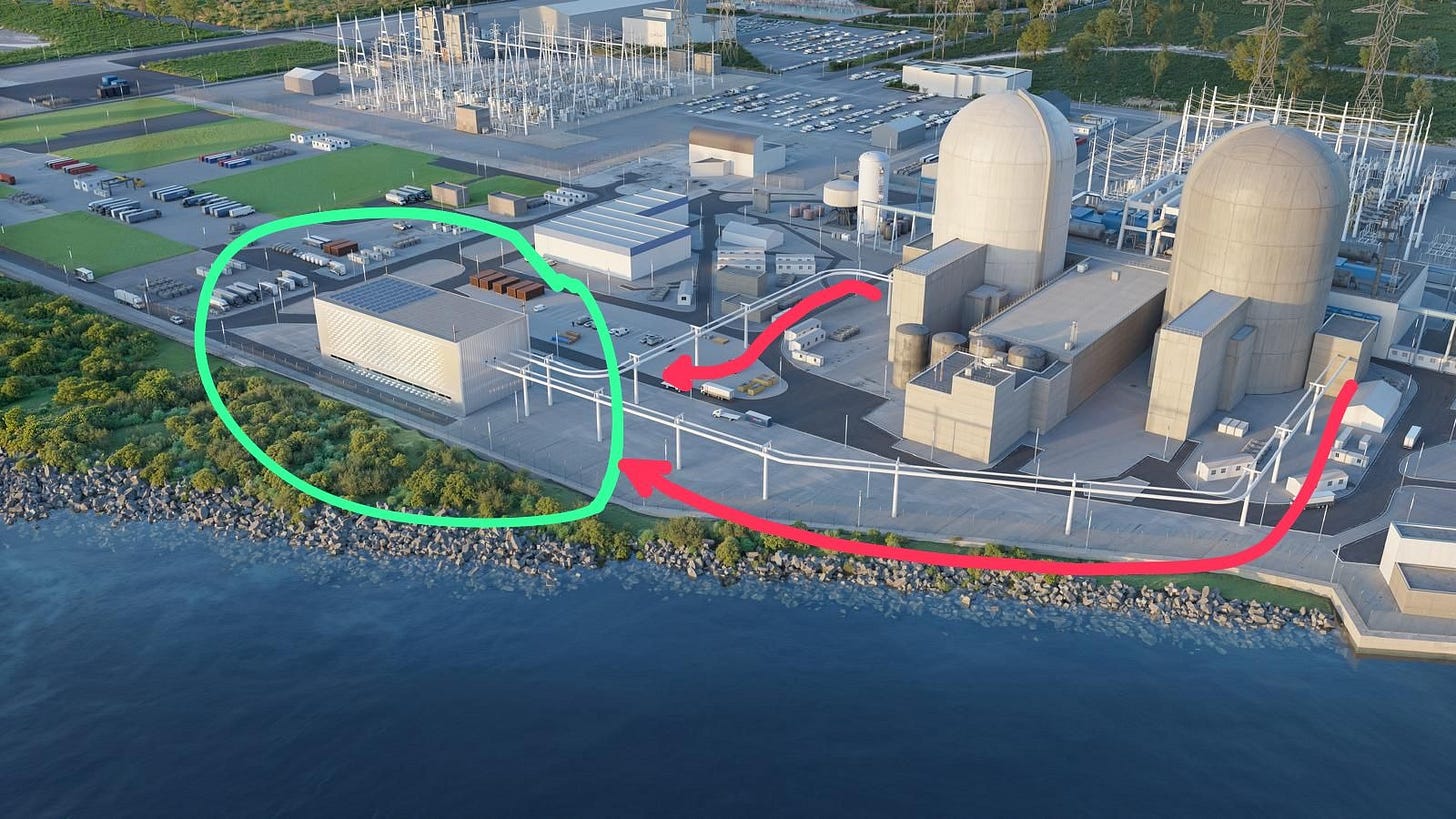

Alva’s approach avoids the traditional uprate bottleneck by building a separate standardized 250MW Second Turbine Generator Plant (2TGP) building diverting incremental steam from an uprated core without touching the existing turbine centerline. Most of the construction happens on a conventional, non nuclear island using mature supply chains and firm fixed price engineering, procurement, and construction contracts, leaving the outage window limited to a short tie in during a normal refueling cycle.

Compared to a cohort of first of a kind nuclear steam supply system startups that accessed public markets through SPAC mergers and achieved substantial valuations in the hundreds of millions on compelling nuclear narratives this approach sounds deliberately boring. But perhaps boring is what our current moment demands. The question is whether the American nuclear zeitgeist can resist the allure of novelty long enough to pluck the low hanging gigawatts hiding in plain sight.

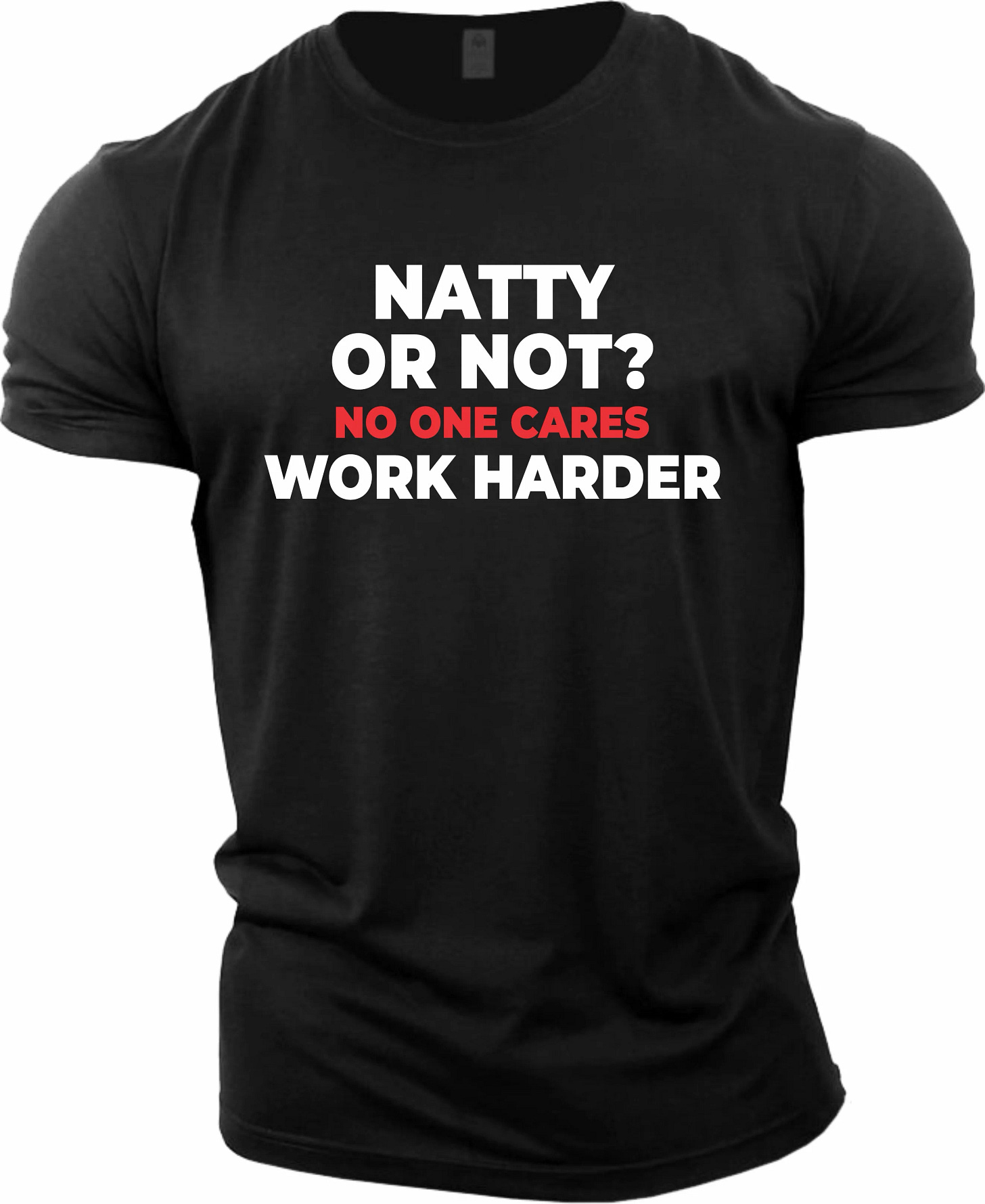

The uprate asymmetry: BWRs juiced, PWRs stayed natural

The United States nuclear fleet has already added roughly 7GW of capacity through uprates. More than two thirds of that came from boiling water reactors (BWR), which represent only about a third of the operating fleet by unit count. The average BWR in the United States now operates at 160MW above its original licensed thermal power. Some units, particularly in Sweden, have pushed uprates past thirty percent.

Pressurized water reactors, by contrast, have barely moved. A handful of plants have completed small stretch uprates in the 2-4% range. A few larger projects happened in the 1970s and around 2010. The Westinghouse four-loop PWR, which is the single most common nuclear steam supply system in the United States by installed gigawatts, has never completed what the NRC classifies as an extended power uprate above 7%.

This asymmetry is not because PWRs are harder to uprate. The explanation is historical and institutional. General Electric (GE) spent decades refining its understanding of multiphase flow in BWR cores, codifying that knowledge and then systematically carrying those analytical approaches through the regulatory process. By the time they were approved, utilities had a clear, repeatable path to extract more power from the same core geometry.

PWR vendors and utilities, for reasons that had more to do with regulatory caution and shifting business priorities than with physics, never invested in the same systematic effort. The result is a technical arbitrage where core thermal margins and fuel performance allow higher power operation within existing licensing limits, but the industry has lacked a standardized engineering package and industrial execution model to make uprates routine rather than bespoke.

If the opportunity has been sitting there for decades, why did nobody pursue it systematically before? The answer has less to do with engineering than with political economy. For much of the 2000s and 2010s, there was no price signal to reward incremental nuclear output. Load growth was flat or declining in many markets, including deregulated ones where nuclear plants delivered reliability and fuel security but were compensated as low value baseload. Natural gas was cheap, and utilities that maintained nuclear fleets optimized for operations and maintenance cost reduction rather than capital investment to expand output.

Lastly, the project delivery organizations that once executed complex plant modifications had been hollowed out or disbanded, and capital markets placed little value on incremental nuclear megawatts when combined cycle gas plants were faster and cheaper to build and were positioned to capture the highest value tiers in deregulated markets by offering dispatchable capacity and ancillary services.

Why the margin exists: computers, steam generators, conservative assumptions

When Westinghouse and Combustion Engineering designed large PWRs in the late 1960s, computational tools for reactor thermohydraulics were primitive. Safety analyses stacked conservative assumptions because uncertainties could not be resolved with higher fidelity models.

In the interim two things have changed. Operating experience accumulated over thousands of reactor years and modern neutronics codes and thermal hydraulic simulations model core behavior with precision impossible in the slide rule era. A reactor designed in 1968 to very conservative margins can now demonstrate it has been operating well within actual physical limits.

The other major variable is steam generator technology. Early designs were prone to tube fouling, corrosion, and plugging. By the 2000s, the industry mastered steam generator replacement during scheduled outages, often upgrading to designs with better materials and more heat transfer area. A new steam generator with greater thermal capacity pulls more heat from the reactor coolant system without changing anything nuclear.

These dynamics mean many PWRs are constrained not by reactor physics, but by secondary side equipment that was never optimized for higher output and is replaceable during maintenance windows.

Feed water heaters, condensers, and solving the outage bottleneck

The irony of nuclear power uprates is that most of the limiting components are not nuclear grade. Feed water heaters, condenser tube bundles, and main turbine capacity are all balance of plant equipment subject to conventional power generation standards, not 10 CFR 50 Appendix B quality assurance.

This matters because it changes the cost structure and the supply chain. A nuclear grade reactor pressure vessel head replacement is a multi-year procurement involving specialized forging, ASME Section III N-stamp fabrication, and a narrow vendor base. A feed water heater replacement is a large industrial heat exchanger that power plants replace routinely, procured from a much broader supplier ecosystem, installed during a refueling outage with craft labor that does not require nuclear-specific training for most of the work.

However, traditional uprates face a brutal execution problem. Accommodating additional steam from an uprated core often requires upgrading or replacing the main turbine centerline, which can take a plant offline for many months, and in some cases more than a year, while large rotating components are removed, replaced, and recommissioned.

Gigawatt-scale turbine replacements are supply chain nightmares, with seven-year lead times for forgings and machining across global vendors. Refueling outages are already tightly choreographed events with narrow critical paths, and adding major turbine work creates cascading dependencies where a late component delivery or installation complexity can spiral into months of lost generation with average losses of ~1 million dollars per day offline.

The approach being pursued by Alva attempts to sidestep this by standardizing the secondary side uprate package and decoupling it from the outage critical path. Instead of upgrading the existing turbine centerline, the additional steam from the uprated core gets diverted to a new standardized 250MW steam turbine plant, the Second Turbine Generator Plant (2TGP), built outside the protected area while the reactor stays online. During a normal refueling outage, the new plant gets tied into the steam and feedwater headers. To the existing balance of plant equipment, it appears as if the uprate never happened, since the original systems continue operating at their pre-uprate design basis.

Where does the second turbine island actually go? The answer is that many United States sites were originally planned for additional units that were later canceled. Those cancellations left brownfield or greenfield space already served by transmission infrastructure, cooling water systems, and heat rejection capacity.

This configuration changes the economics substantially. The bulk of the work happens on a greenfield site using non-nuclear construction standards, which allows firm fixed-price EPC contracts of the kind that companies routinely execute for combined cycle gas applications. The outage duration drops from months to the time needed for steam generator replacement work that many plants already do in under 30 days. The 200 to 300MW steam turbine supply chain, which has been building these units globally for over a century, is far broader than the narrow vendor base for gigawatt-scale reactor centerline components.

The goal is to build off of examples like Bechtel and SGTe who turned multi-year replacement projects into highly choreographed outages that could swap out a 400-ton steam generator in under thirty days. The learning curve was steep, but once the process was standardized, costs and schedules dropped by an order of magnitude. The first steam generator replacement at Surry in the 1970s took longer than 14 months. By the 2000s, the industry was completing them in 26 days.

The same learning curve logic applies to uprates. The first few projects will be slower and more expensive as engineering margins get validated and installation procedures get refined. By the fifth or sixth unit, the process could become routine, and the economics start to look very different from traditional megaproject math.

Are Uprates Parasitic?

The entire uprate model rests on an assumption about asset longevity. Many of the three-loop and four-loop PWRs being discussed are 1960s and 1970s vintage. Some are well into their second license renewal period. How long can these plants realistically run, and does pushing them to higher thermal power shorten that operating life?

Alva assumes conservatively that uprate economics must clear over a twenty year window, even though many units are likely to operate longer based on subsequent license renewals and ongoing reactor pressure vessel embrittlement monitoring. To date, neither the Nuclear Regulatory Commission nor the utility industry has identified hard material limits that would preclude further extensions, and surveillance reactor vessel capsule data continues to support long term operation.

The asset life question also has a portfolio dimension. The U.S. PWR fleet is not uniform in age. Watts Bar Unit 2 entered service in 2016, Seabrook in 1990, and Vogtle Units 1 and 2 in the early 1990s. These are all Westinghouse four loop reactors, some younger than the engineers now designing uprates for them, spanning an opportunity set that includes plants with decades of remaining life alongside those closer to the end of their initial operating horizon.

Second, and more interesting, is the claim that the uprate configuration can actually improve reliability rather than degrade it. The stress on rotating machinery in a traditional uprate comes from forcing the existing turbines, pumps, and heat exchangers to handle more flow and higher thermal loads. That is where you see unexpected consequences, unplanned trips, thrown turbine blades, and accelerated wear.

By diverting the additional steam to a separate turbine island, the existing balance of plant equipment continues operating at its original design conditions. The reactor coolant pumps run at the same speed. The main turbine sees the same steam flow it always has. In some cases, plants that had been pushing their legacy equipment by a few percent to squeeze out marginal gains can now dial that back, sending the extra steam to the new turbine and recovering reliability margin on the old equipment.

The nuclear steam supply system itself, according to this argument, is not being stressed in the conventional sense. The new steam generators are designed for the higher thermal duty. The reactor core operates at a higher power level, but modern fuel can handle it, and neutron flux increases are accounted for in embrittlement calculations. In some configurations, the primary system actually runs slightly cooler than before because the improved heat transfer pulls more energy out at lower temperatures.

Steam generator replacement has historically been life-extending rather than life-consuming. If the uprate layers additional revenue on top of that investment without imposing new mechanical stress on the equipment that actually fails, the model works.

What actually drives the schedule?

A claimed five-year timeline from engineering to commercial operation does not immediately sound transformational. Combined cycle gas plants can go from greenfield to energization faster than that in many jurisdictions, and the pitch is that uprates could potentially beat gas on speed. What takes so long?

The answer is procurement, specifically steam generator fabrication. There has not been a robust market for new steam generators in recent years, and the vendor base needs time to scale back up. Unlike balance of plant components, steam generators are nuclear-grade pressure vessels subject to ASME Section III requirements, and the forging and tube bundle fabrication cannot be rushed. That procurement dominates the critical path for the first project.

The critical difference from traditional uprates is what is *not* on the critical path. All of the balance of plant construction, the turbine island fabrication, the installation of condensers and feedwater heaters, happens in parallel in the Second Turbine Generator Plant while the reactor stays online. By the time the new steam generators are ready and the plant goes into a refueling outage, the 2TGP is already built and tested. The outage itself only needs to accommodate the steam generator swap and the tie-in to the new headers, work that fits within a normal refueling window that the plant would be taking anyway.

This architecture allows parallelization. Once the first project validates the design and establishes the supply chain, subsequent projects at other sites can proceed simultaneously. The developer is not waiting for one plant to finish before starting the next. Multiple steam generator sets can be in fabrication for different sites. Multiple turbine islands can be under construction. The bottleneck shifts from sequential field construction to fabrication capacity, and fabrication scales faster than field work.

There is also an option value embedded in the model. If a hyperscaler wants power faster and is willing to pay for acceleration, the plant can take an earlier outage, compressing the overall schedule at the cost of higher near-term spending. That flexibility does not exist in new build projects, where the critical path is locked in by the construction sequence.

Whether five years is realistic for the first project is testable. Whether the timeline compresses for subsequent units depends on how well the standardization actually works and whether the steam generator supply chain can ramp without hitting quality or delivery problems. The schedule claim is aggressive but not obviously implausible, and it is far more credible than any of the timelines being quoted for first-of-a-kind reactor designs.

The Microsoft arbitrage: $116/MWh for 800 megawatts

The demand signal for additional nuclear capacity is no longer theoretical. Microsoft signed a power purchase agreement with Constellation to restart Three Mile Island Unit 1 at a reported price of $116/MWh. That is multiples of the current PJM wholesale clearing price, and it is for 835MW of capacity that was already built, already licensed, and sitting idle.

This price point changes the economics of everything. A nuclear uprate that adds 200-300MW to an existing unit, if it can secure even a fraction of that premium through a long-term PPA with a hyperscaler or large industrial customer, suddenly has a revenue stream that supports very aggressive capital investment.

The reason those prices exist is simple. Data centers need firm, 24/7 power with very high reliability, and although climate policy is on the back burner some still value low-carbon generation to satisfy their corporate commitments and comply with their AI customers’ environmental procurement requirements which is why Constellation can command that kind of premium.

This dynamic is not limited to restarts. An uprate that brings 200-300MW of additional capacity online at an existing site, with an existing transmission interconnection and an operating license already in hand, competes not against wholesale power markets but against the all-in cost of new generation that can meet the same reliability and carbon requirements. In that comparison, uprates start to look very attractive indeed.

The time advantage is also real. A well-executed uprate can go from engineering to commercial operation in 3-5 years, depending on the licensing path and the outage schedule. That is faster than any new nuclear build and faster than most large combined cycle gas plants in contested permitting environments.

If the hyperscalers are serious about expanding their AI infrastructure over the next decade, and if they are willing to pay nuclear premiums to secure that expansion, then there are billions of dollars of potential offtake value sitting in the existing PWR fleet waiting to be unlocked.

A typical 20 percent uprate on a 1,200MW unit adds 240MW, almost the equivalent of a BWRX-300 or roughly three NuScale power modules, at one-fifth to one-seventh the cost and without the construction risk or regulatory complexity of first-of-a-kind designs. Multi-unit stations could add several Alva Second Turbine Generator Plants (2TGPs) the equivalent of multiple SMRs. The entire uprate potential across the PWR fleet represents 20 to 30 small modular reactors worth of capacity, available in three to five years rather than fifteen.

The hidden crux: Competent project delivery organizations

One of the most common objections to nuclear uprates is regulatory risk. The reality is that the NRC has a well-established framework for reviewing power uprates, and utilities have successfully completed dozens of them under both the standardized review process for power uprates and through the license amendment process.

The real question is whether the American nuclear industry can rebuild the kind of project delivery organizations that used to exist at utilities like Florida Power & Light (FPL). The difference between a good nuclear project and a disaster often comes down to the strength of the owner or developer organization, not the reactor vendor. This is the lesson from comparing the construction of nuclear power plants St. Lucie Unit 2 in Florida with Washington Nuclear Project 3 in Washington State. Both were Combustion Engineering reactors with Ebasco as architect engineer, both under the NRC, both starting construction in 1977.

St. Lucie 2 came in under budget in about five years in the post-Three Mile Island context. It was built by FPL working with a couple hundred person internal projects organization whose only job was to deliver new nuclear for the utility.

In sharp contrast, Washington Nuclear Project 3 helped trigger the largest municipal bond default in American history at the time, built by the Washington Public Power Supply System, a loose consortium of dozens of small public utilities that had never built large thermal plants before.

The timing, hardware, vendor, and regulator were identical, yet outcomes diverged because the owner side organization differed in its ability to integrate the work, supervise execution, and enforce discipline.

A project delivery organization is not a contractor. It is an entity that takes responsibility for integrating design, procurement, construction, commissioning, and handover, and that has the authority and accountability to enforce schedule and cost discipline across all of those phases. It sits between the utility that will own and operate the asset and the vendors that supply the hardware. It knows how to read a Primavera P6 project schedule, manage a critical path, run value engineering sessions, and make the hard calls about when to push and when to stop.

This kind of organization does not get built by raising venture capital or hiring consultants. It gets built by doing hard projects, making mistakes, learning from them, and keeping the team together long enough to apply those lessons to the next project.

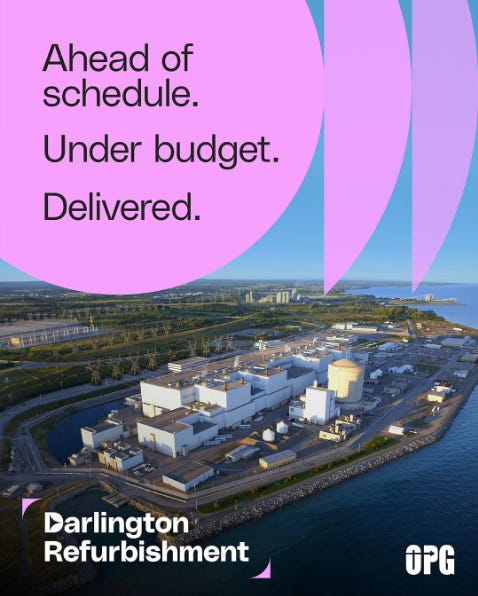

In contemporary terms Canadian utilities, Ontario Power Generation (OPG) and Bruce Power, did not suddenly know how to run billion-dollar refurbishments. They learned by doing them, repeatedly, under enormous public scrutiny, and they kept the institutional memory alive by maintaining continuity in leadership and core staff. Ultimately both OPG and Bruce Power have delivered under budget and ahead of schedule.

The strategy of starting with uprates rather than jumping straight to new builds offers a sequencing that allows organizations to build capability progressively. If a developer can repeatedly bring 200-300MW increments online at multiple sites over the next five years, they will have demonstrated something that almost no one else in the American nuclear sector can claim right now.

Boring is the new radical

The nuclear industry has spent the last two decades chasing innovation in advanced reactors, modular designs and factory fabrication with very little to show for it.

Power uprates at existing PWRs represent industrial execution and process discipline rather than the kind of work that generates TED talks or 500 million dollar SPAC combinations, but they actually put gigawatts on the grid. At this point if the nuclear renaissance is going to be real, it will not be because someone invented a better reactor. It will be because someone figured out how to repeatedly deliver projects on time and on budget, and then scaled that capability across a fleet.

The hardware already exists, the regulatory path is clear, and the demand is there, but what has been missing is the organizational capacity to turn all of that into megawatts. Time will tell whether developers like Alva can execute on the first few projects, prove the model works across different sites and vintages, and build the kind of repeatable project delivery organization that can scale beyond uprates. If they can, the nuclear sector gains something it has lacked for decades: a credible path from concept to commissioning that does not depend on heroic assumptions or government guarantees.

The most boring path to ten new gigawatts might also be the best path, for now.

If this analysis informed your thinking, consider supporting independent nuclear journalism. Make a tax-deductible donation

Discussion about this essay is open to all subscribers. If you have thoughts on uprates, project delivery, or the broader nuclear landscape, share them in the comments.