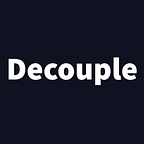

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Army Nuclear Power Program built and operated a string of compact low power 2-10 MW reactors aimed at a promise that still sounds familiar today, less dependence on fuel logistics and reliable power in hard places.

The program produced real machines and real experience, including functioning reactors buried under a glacier in Greenland, a research base in Antarctica, as well as remote continental sites in Wyoming and Alaska. Ultimately the program was cancelled not because the Army lacked engineering talent but rather because the total system never beat the alternative, even in some of the most austere, high cost environments imaginable.

The unique challenges posed by radiation and decay heat management meant that diesel won on logistics and simplicity. Outside of submarines, aircraft carriers and icebreakers, all applications where nuclear offers a step change in military capabilities over alternative fuels, small land based reactors never earned their keep.

Project Pele, an ongoing US Army effort to produce a mobile high temperature gas reactor, is the bridge between eras. It is not a commercial product but rather a prototype and a forcing function, designed to drive learning into hardware, licensing, fuel qualification, transport and all of the other unglamorous interfaces that never appear in investor decks.

The Janus program, named after the Roman God of transitions, is the next step, and it is qualitatively different.

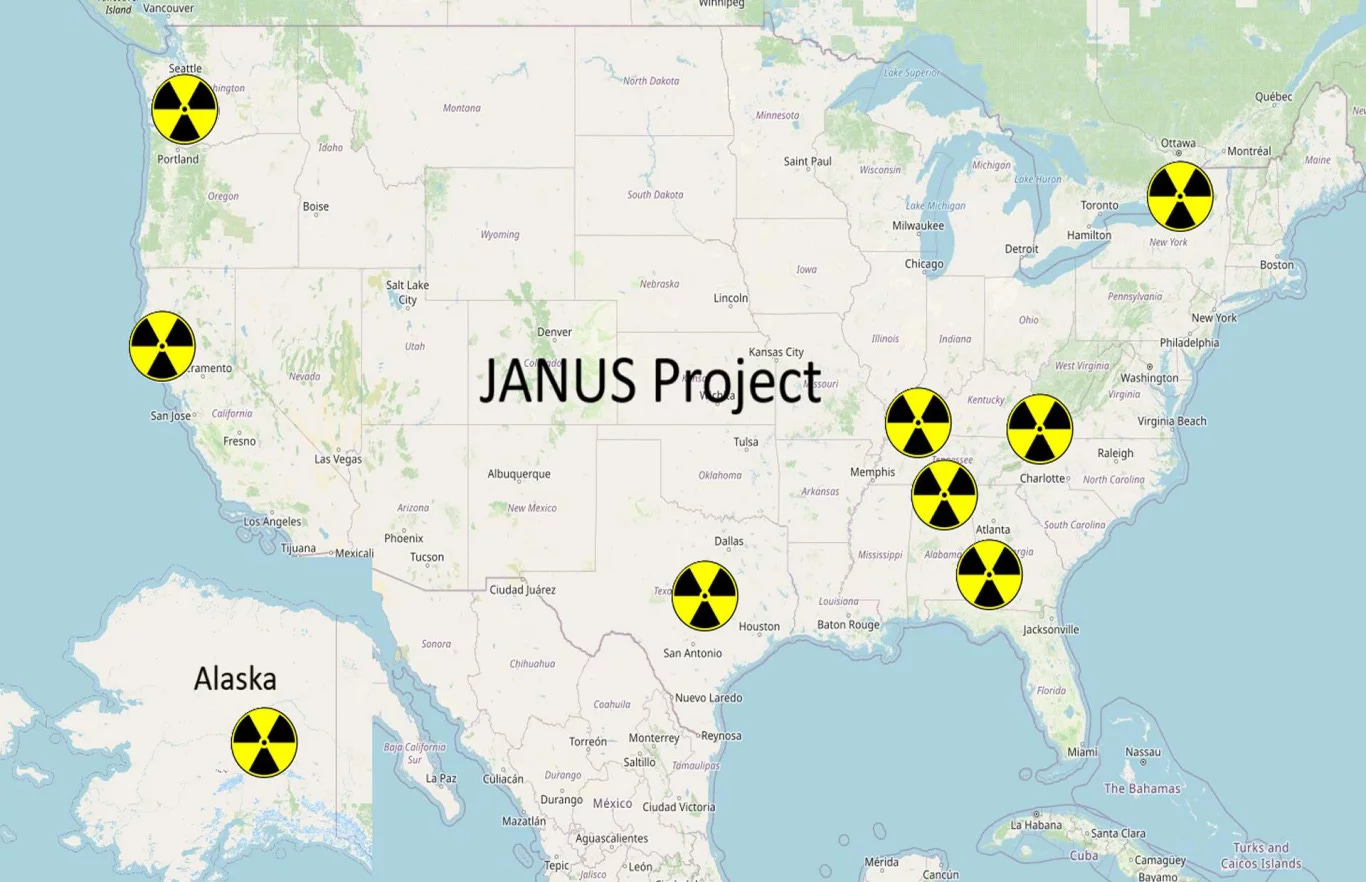

It is a United States Army procurement program intended to act as industrial policy to transition a nascent microreactor industry from isolated demonstrations into commercial services. It does this by selecting multiple private reactor vendors, providing them with milestone based federal funding to design, build, license, deploy, and operate first of a kind microreactors, and then requires those reactors to sell electricity to continental US (CONUS) Army installations under market rate power purchase agreements.

The Army acts as an anchor customer, not by guaranteeing long term overpayment for power, but by subsidizing early technical and regulatory risk while enforcing price discipline once reactors enter operation.

This is the wager and it all hinges on the question of whether microreactors can ever compete in remote environments with diesel generators let alone with the cost of grid electricity in the continental USA. It is a very high bar indeed.

Janus as COTS for Nuclear

The Army is not pretending that a 1-10MW reactor can be brought to commercial operations on a normal power purchase agreement. CONUS Military installations are typically constrained to pay near local market rates for electricity. In much of the continental United States, including most of the bases identified by Janus, that means something on the order of 12 cents/kWh.

At 1MW, that translates into roughly $120 per hour of gross revenue. That is clearly not enough to pay for licensed operators, security, maintenance, capital recovery, decommissioning reserves, and backend fuel handling, let alone repay the enormous fixed costs of first of a kind nuclear hardware.

Combine this with the fact that FOAK microreactors, most of them non light water reactors, are unlikely to hit the 93% capacity factors we now take for granted in the experienced PWR/BWR fleet which will result in significant loss of revenue.

Janus attempts to give microreactors their best chance by shifting the subsidy to the front end. To accomplish this it is modelling itself on Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS), the NASA initiative in the early 2000s that restructured how the United States procured launch capability. This was the program that enabled SpaceX which now accounts for more than half of all global orbital launches. Instead of building rockets in house or reimbursing contractors under cost plus contracts, COTS relied on fixed milestone payments, hard down selects, and vendor replaceability to force convergence through execution rather than promise.

COTS subsidized learning rather than launches. Firms were paid only when they demonstrated specific capabilities such as engine tests, integrated systems, orbital insertion, and cargo delivery. Cash was released when milestones were met, not when money was spent. The government absorbed early technical risk while refusing to guarantee long term revenue, ensuring that companies unable to close the gap between demonstration and service pricing failed quickly.

Janus is attempting to apply that same logic to microreactors. The Army is not trying to pick a winner in advance, nor is it pretending that electricity sales can fund first of a kind nuclear systems. Instead, it is using milestone based funding to buy down early uncertainty while deliberately constraining back end power prices to market rates in order to preserve commercial discipline.

Why Janus Starts on the Easiest Battlefield

Janus is about moving from demonstration to service, with commercial vendors selling electricity to CONUS Army installations.

This approach seems to implicitly rebut the most common microreactor narrative, that the killer application is the remote outpost and the fuel convoy where cost of diesel and lives at risk from fuel convoys justify the cost and complexity of nuclear. However the stated reason to deploy at CONUS bases is that this is a safer training ground. If you were to drop a FOAK microreactor into the most logistically hostile environment possible, you guarantee that every weak interface will be stressed simultaneously.

While Pele exists to reveal those weak interfaces, Janus exists to manage them.

Continental installations are grid connected and close to industrial services. They allow normal American logistics and normal maintenance ecosystems. The sequence is to learn to design and build and operate domestically and then earn deployment overseas in places like Guam or remote forward operating bases.

Technology Choice Based on Logistics

One of the clearest signals from the program is that Janus is not a closed club. With over fifty companies expressing interest, the selection process will be strict. Either the Army builds a funnel that rapidly converges on a small number of credible teams, or it splinters the already scarce nuclear engineering talent of the country across dozens of parallel reinventions of the same materials, the same components, and the same regulatory arguments.

Janus plans to address this with a deliberate, multi stage downselect process. The first round will quickly narrow the field. The next deepens technical scrutiny. Pitch sessions may become Rickover-esque interrogations, not the VC marketing exercises we are so familiar with.

Janus is not truly technology agnostic, even if it avoids picking a single winner at the outset. Light water reactors are not excluded by ideology but deprioritized due to their need for abundant onsite water and the Army’s desire for technology that comes without any major siting limitations.

There is also a quieter constraint, rail dependency. Large commercial and naval reactors rely on rail spurs for heavy components. Janus wants truck transport. That imposes hard dimensional and weight limits, bridge ratings, tunnel clearances, and radiation constraints at specified distances.

This creates a standardization pressure that mirrors early rocketry with a handful of viable envelopes. Designs that cannot fit them will not scale.

Pele’s Real Legacy, Logistics and Fuel

By the time Project Pele and its supporting infrastructure are fully counted, the total cost will be on the order of one billion dollars. That figure is sometimes cited as evidence of the near unsurmountable economic challenges of microreactor development, but the money has not been used to buy a single microreactor. In much the same way that decades of extraordinarily expensive NASA’s spaceflight programs created the technical, regulatory, and industrial substrate that later made SpaceX’s success possible, Project PELE hopes to play a similar role for microreactors involved in the Janus program.

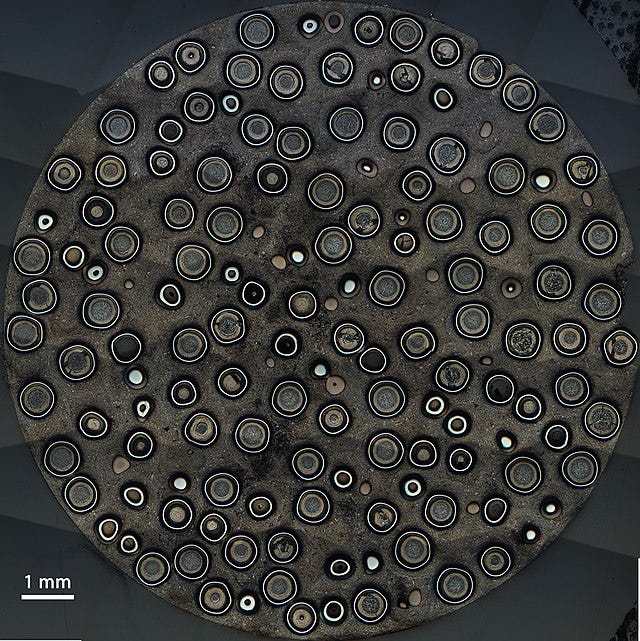

One of the clearest examples is fuel logistics. Pele exposed a problem that is easily missed, how to move an entire core, not a handful of TRISO fuel elements, across the country without introducing breakage, criticality risk, or regulatory surprises. Earlier Department of Energy shipments were effectively artisanal, designed around small quantities and bespoke handling.

Once scale enters the picture and tens of thousands of TRISO fuel elements must be transported together, packaging itself becomes a nuclear design problem. Because the moderator is embedded in the fuel, container geometry, packing density, water ingress scenarios, and inspection tolerances all directly affect criticality assumptions and safety cases.

Decisions long since made for conventional fuel suddenly shape licensing, shipping approvals, and acceptance criteria at destination, forcing engineering discipline into what had previously been treated as logistics.

Why the SpaceX Analogy Only Goes So Far

If Janus is an attempt to apply the COTS model to nuclear, then its limits matter as much as its promise. The analogy holds at the level of procurement and incentives, but it faces challenges on economics and time constants.

As Ethan Chaleff has pointed out, orbital launch is a scarce, high value service where each technical success directly expands the addressable market and unlocks higher value missions. Baseload electricity, by contrast, is a commodity whose price is largely set externally, and at the 1-10 megawatt scale even flawless technical execution produces limited revenue relative to nuclear’s inherent costs. While improved reliability and risk reduction can open additional niche markets such as remote sites or specialized users, there is no single technical milestone analogous to a successful launch that causes a step change in pricing power or fundamentally transforms the economics of the service.

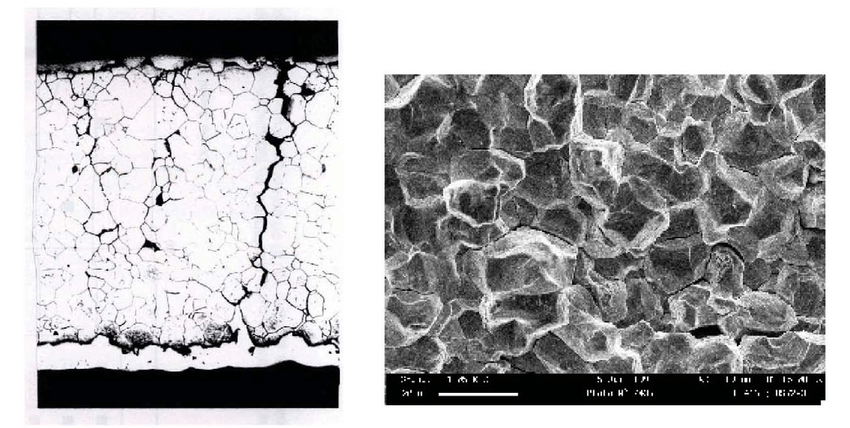

The difference in iteration speed compounds this mismatch. Rockets fail in seconds and teach quickly, allowing redesign on short cycles. Nuclear systems often fail late and teach slowly. In pressurized water reactors of the 1960s, nickel chromium iron Alloy 600 was widely used in steam generator tubing. Its susceptibility to primary water stress corrosion cracking only became apparent after decades of operation, long after it had been widely deployed at fleet scale. Correcting that mistake required an additional decade of inspections, replacements, and ultimately wholesale substitution with higher chromium Alloy 690 components at enormous cost, illustrating the slow, amortized learning cycle of nuclear engineering.

SpaceX experienced an analogous materials lesson on a radically compressed timescale. Early Falcon 9 vehicles used composite overwrapped pressure vessels (COPV) for helium storage inside cryogenic oxygen tanks. The AMOS-6 pad explosion in 2016 caused by oxygen freezing and igniting within the composite overwrap, forced a fundamental redesign of the COPV architecture, materials, and loading procedures. Within months, SpaceX introduced a new pressure vessel design and operational envelope, eliminating the failure mode before it could propagate across a large operational fleet.

One sector learned in months because failure was fast, observable, and relatively cheap. The other learned over decades because degradation was slow, distributed, and only visible after long service exposure. Microreactors inherit that slow pace of nuclear iteration regardless of their small size.

Janus therefore applies the SpaceX playbook under unusually tight constraints. It can impose discipline, force early confrontation with logistics and materials reality, and test whether a narrow set of designs can survive without permanent subsidy. What it will struggle to do is compress nuclear physics, regulatory time, or the economics of baseload power.

Seen this way, Janus is not a moonshot modeled on SpaceX’s outcome. It is a stress test modeled on SpaceX’s method, designed to determine whether microreactors can survive the most forgiving version of the market before anyone asks them to survive in a warzone.