Every few decades, civilian nuclear propulsion at sea reappears as a serious proposal, often catalyzed by a familiar external pressure. Rising fuel costs, geopolitical disruption, or, more recently, climate driven decarbonization targets renew interest in an energy source with extraordinary power density, infrequent refuellings, and sustained high power output which, on paper, appear tailor made for long haul shipping.

And yet, after seventy years of experiments, prototypes, and near misses, nuclear propulsion remains confined to narrow use cases: submarines, aircraft carriers, icebreakers, and a single cargo ship on the Russian Northern Sea Route operating at the margins of the commercial world.

This recurring pattern is not accidental. It reflects a stable equilibrium between what nuclear propulsion offers at sea and what it costs, institutionally and logistically as much as financially, to deploy it. Climate pressure raises the value of zero emission propulsion and keeps nuclear shipping returning to the agenda, but it does not alter the underlying physics or economics. Where nuclear propulsion removes a binding physical constraint, it transforms operations. Where its advantages are incremental rather than decisive, it struggles to justify its burdens.

Where Nuclear Propulsion Wins Decisively

Submarines are the cleanest case. Nuclear propulsion did not merely improve submarines, it redefined them. Diesel electric submarines were essentially surface ships with the ability to submerge. They were constrained by snorkeling, refueling, low speed, and limited endurance. Nuclear propulsion erased those constraints simultaneously. Speed, stealth, endurance, and global reach all shifted by orders of magnitude, not by margins. The constraint on submersion time became calories for the crew, not fuel for the vessel.

Aircraft carriers follow a similar logic, though for different reasons. Carrier aviation imposes extreme power demands. Launching aircraft from a short deck requires sustained high speed into the wind, and fuel consumption rises sharply with speed. For large displacement ships, propulsion power scales roughly with the cube of speed, meaning that doubling speed can require on the order of eight times more fuel. For a carrier that must repeatedly generate high wind over deck to support flight operations, nuclear propulsion removes a severe fuel and endurance constraint.

Another underappreciated reason nuclear propulsion makes sense for carriers is fuel volume. The conventionally powered John F. Kennedy 1968-2007, for example, required about 3.2 million gallons of diesel for the ship itself, in addition to roughly 3 million gallons of JP-5 aviation fuel for its air wing. Together that is almost ten Olympic swimming pools of fuel.

Nuclear propulsion therefore frees vast internal volume for aviation fuel, weapons, and operational flexibility, which becomes a decisive advantage for sustained air operations.

Nuclear icebreakers represent a third category where propulsion is mission enabling rather than incrementally beneficial. Icebreaking imposes continuous, high power demands over long durations, often in remote regions where refueling is impractical or impossible and failure carries severe operational risk. Nuclear propulsion allows icebreakers to operate for extended seasons with sustained power output independent of fuel supply. In this context, nuclear propulsion solves a hard physical constraint rather than optimizing around cost.

In all three cases, nuclear propulsion enables missions that otherwise become impractical or impossible. Where it merely improves efficiency or endurance at the margin, its advantages fade.

Surface combatants such as cruisers illustrate the limits clearly. Unlike submarines, they already operate within a dense replenishment ecosystem. Aircraft carriers must be resupplied with aviation fuel every few days during high tempo operations, and that same logistics train routinely delivers fuel to the escorting cruisers and destroyers.

Refueling surface combatants at sea is therefore not a binding constraint. Nuclear powered cruisers gained endurance and speed, but they did not gain a fundamentally new mission or operating concept. They still required large crews, complex maintenance, and expensive mid-life refueling overhauls that imposed long periods out of service.

Once the decisive logistical advantage disappears, nuclear propulsion becomes difficult to justify. Around ten percent of US cruisers were nuclear powered during the Cold War. Ultimately, they were all decommissioned not because they performed poorly, but because their incremental benefits no longer outweighed their incremental costs as budgets tightened.

Civilian Shipping and the Limits of the Nuclear Advantage

Civilian shipping pushes this logic even further. Cargo ships exist to move mass at the lowest possible cost per tonne mile. Fuel is important, but it is only one component of a broader cost structure that includes capital cost, crew size, insurance, port access, regulatory compliance, maintenance regimes, and schedule reliability. Unlike submarines or aircraft carriers, civilian cargo ships do not exist to deliver unique capabilities. They exist to minimize cost within an intensely competitive global system.

Nuclear propulsion dramatically reduces fuel logistics, but it increases almost everything else. That tradeoff sits at the core of why civilian nuclear shipping repeatedly proved technically viable yet economically fragile.

During the Cold War, only four civilian nuclear powered cargo ships ever entered service. Each was launched for a different reason. Each functioned technically. Each was ultimately withdrawn for economic or political reasons rather than technical failure.

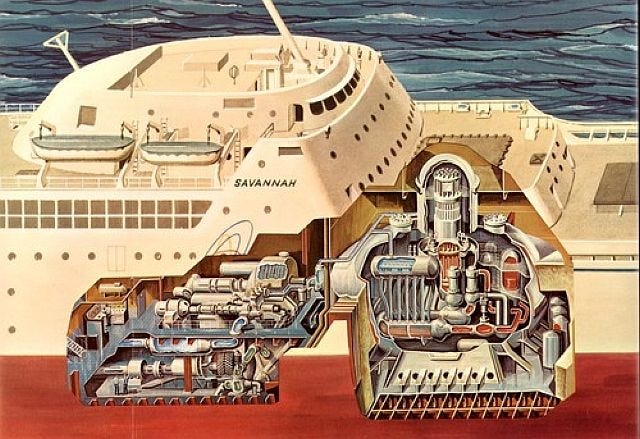

The NS Savannah

The first was the Savannah, launched in 1959 and brought critical in 1961 as part of the Eisenhower administration’s Atoms for Peace program. It was conceived less as a competitive cargo vessel than as a floating demonstration of peaceful nuclear technology. The ship carried passengers and cargo, operated a pressurized water reactor designed by Babcock and Wilcox, and entered service in 1962. Over the 1960s it visited dozens of domestic and foreign ports and transited the Panama Canal, forcing regulators to invent procedures for nuclear ship entry, low power maneuvering, tug escort, and liability coverage. From an engineering standpoint the ship operated as intended, and as a diplomatic project it achieved its purpose, but it was never designed to compete economically with conventional cargo vessels. Built before containerization and operated with higher crew requirements and bespoke regulatory treatment, Savannah was decommissioned in 1970 once its demonstration value was exhausted.

The Otto Hahn

West Germany’s Otto Hahn, launched in 1968, represented a more serious attempt to integrate nuclear propulsion into a working cargo vessel. Unlike Savannah, it was designed from the outset as an ore carrier rather than a political exhibit. Its reactor, also designed by Babcock and Wilcox, was an integral pressurized water reactor that compressed the primary system into a single pressure vessel, reducing volume, mass, and piping complexity. Otto Hahn operated successfully for years and demonstrated that nuclear propulsion could function reliably in commercial service. Yet its economics remained marginal. Nuclear trained crew commanded wage premiums, regulatory oversight remained exceptional rather than routine, and access to key maritime chokepoints remained restricted, with Otto Hahn denied transit through both the Panama and Suez Canals while nuclear powered. When fuel prices fell and conventional propulsion improved, the narrow economic window closed. The reactor was removed and the ship continued service under diesel propulsion.

The Mutsu

Japan’s Mutsu, launched in 1970 and completed in 1974, exposed a different vulnerability. During initial low power testing at sea, a shielding design flaw allowed fast neutrons to stream into unintended areas of the ship. There was no fission product release, but radiation was detected where it should not have been. Correcting the problem required substantial additional shielding, structural modifications, and reconfiguration of internal spaces. The technical issue was fixable. The political damage was not. Fishermen protested, ports refused entry, and national headlines declared radioactive leakage. After years of redesign and delay, Mutsu operated only briefly before being shut down, illustrating how unforgiving civilian nuclear shipping could be.

The Sevmorput

The most durable example was the Soviet Union’s Sevmorput, launched in 1986. Unlike its Western counterparts, it occupied a niche, the Northern Sea Route, where nuclear propulsion addressed a genuine physical constraint rather than offering a marginal economic improvement. Designed as a Lighter Aboard Ship (LASH) vessel, it carried cargo in self contained barges that could be offloaded to shallow, undeveloped, or icebound ports inaccessible to conventional deep draft ships. While not a true icebreaker, it was built with a reinforced ice class hull that allowed it to operate in heavy ice conditions and transit icebreaker opened channels along the Northern Sea Route. In Arctic waters, refueling is difficult, weather is unforgiving, port infrastructure is sparse, and sustained propulsion power is operationally essential. Nuclear propulsion offered a functional advantage that conventional alternatives struggled to match.

Even here, the equilibrium remained fragile. Sevmorput spent long periods laid up, and its utilization depended heavily on state support, Arctic traffic levels, and geopolitical priorities. It did not establish a template for global nuclear cargo shipping. It carved out a narrow role where alternatives failed physically, not merely economically. That pattern aligns with Russia’s broader nuclear icebreaker fleet, where nuclear propulsion succeeds by removing binding physical constraints rather than marginally improving fuel economics.

Taken together, these cases reveal a consistent pattern. Civilian nuclear propulsion worked technically. It failed economically except where it solved problems that conventional propulsion could not.

Decarbonization Pressure Changes the Debate, But Not the Physics

The renewed interest in nuclear shipping today has been driven primarily by emissions constraints rather than fuel logistics. The International Maritime Organization has advanced decarbonization targets that push commercial shipping toward net zero emissions by mid century. Alternative fuels such as ammonia, methanol, and synthetic hydrocarbons impose penalties in energy density, handling risk, infrastructure requirements, or cost.

Against this backdrop, nuclear propulsion reemerges as one of the few options capable of eliminating operational emissions without reducing range, speed, or payload. That shift matters, but it does not dissolve the underlying cost and complexity problem. Decarbonization increases the value of zero emission propulsion, yet it does not remove the institutional overhead associated with nuclear systems.

Political resistance further complicates the picture. Efforts by Donald Trump to pressure the International Maritime Organization to retreat from its decarbonization agenda underscore a key difference between nuclear safety regulation and climate policy. Nuclear safety enjoys broad international consensus. Maritime decarbonization does not. If climate policy fragments along geopolitical lines, the main incentive structure favoring nuclear propulsion weakens significantly.

The central question remains whether climate pressure becomes strong enough to outweigh cost sensitivity in a sector defined by thin margins and relentless competition.

Advanced Reactor Concepts Reappear, but the Old Tradeoffs Remain

Renewed interest in nuclear shipping has revived familiar reactor concepts. Molten salt reactors, high temperature gas reactors, and other advanced designs are often presented as better suited for maritime use, promising lower pressure operation, inherent safety, or improved flexibility. These arguments are not new. Similar concepts were explored extensively during the early decades of naval nuclear development.

That experience produced a clear outcome. After testing a wide range of unconventional reactors, pressurized water reactors emerged as the near universal solution not by convention, but by elimination. Liquid metal cooled reactors were operated at sea in both US and Soviet submarines, while organic cooled and other exotic concepts were tested in prototype form. None delivered a decisive improvement once size, power density, reliability, maintainability, and crew requirements were fully considered.

Water’s role as both coolant and moderator enables compact, high power density cores that integrate efficiently into ship hulls. At sea, compactness directly affects stability, shielding mass, and usable volume. Designs with lower power density impose cascading penalties that grow rapidly in space and weight constrained environments.

Water cooled systems also align naturally with the marine environment. The ocean is an effectively infinite heat sink, and water cooled reactors tolerate water ingress. By contrast, gas cooled reactors suffer from low power density, while molten salt reactors embed fission products within circulating fuel. In such systems, the entire primary circuit becomes highly radioactive, turning pumps, valves, and heat exchangers into persistent radiation sources and complicating routine maintenance.

Technology readiness carries disproportionate weight at sea. Maritime reactors must endure constant motion, vibration, and long operating intervals with limited maintenance access. Pressurized water reactors have accumulated decades of operational experience under these conditions. Advanced reactor concepts have not.

Advanced reactors may eventually find a role in nuclear shipping, but history suggests that success will depend on demonstrated performance rather than assumed superiority. The persistence of pressurized water reactors reflects a fit between physics, engineering, and operational reality that remains largely unchanged.

A Narrow Commercial Niche, and an Aviation Analogy

If civilian nuclear shipping has a future beyond state owned icebreakers and military auxiliaries, it is likely to resemble a narrow corridor rather than a broad transition.

One plausible configuration involves very large vessels powered by tried and tested marine PWRs operating between a small number of dedicated ports, with specialized crews, standardized regulatory frameworks, and predictable routes. In that sense, nuclear shipping begins to resemble a hub and spoke model, not unlike the Airbus A380 concept in aviation.

The A380 was optimized for high volume routes between major hubs, trading flexibility for efficiency at scale. Its failure in passenger aviation reflected the rise of point to point travel and the premium placed on operational flexibility rather than pure capacity. Shipping differs in important ways. Cargo is less sensitive to frequency, and ports already function as aggregation nodes. But the structural lesson remains. Platforms optimized for extreme scale succeed only where traffic density, infrastructure, and demand stability align.

This leaves open the possibility that ultra large crude carriers or container ships operating on fixed routes between energy or resource hubs could justify nuclear propulsion under extreme decarbonization pressure. Even then, success would depend on unusually stable demand, supportive regulation, and some degree of state backed risk absorption.

That is a narrow niche, not a general solution.

Cost, Complexity, and the Persistent Constraint

Nuclear propulsion at sea has always been constrained by the same forces. It adds complexity to vessels designed to minimize it. It introduces regulatory and political risk into industries that operate on thin margins. It solves problems that become decisive only in extreme operational environments.

Decarbonization pressure increases its appeal, but it does not transform its economics. The history of nuclear shipping suggests not impossibility, but selectivity. Nuclear propulsion thrives where its advantages overwhelm its burdens. Everywhere else, it remains a solution in search of a problem large enough to justify it.

That reality has not changed, even as the climate imperative has waxed and waned.

If this map helped you navigate the tradeoffs, a like and subscription help keep Decouple critical