There is a line I have been using for years: it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than to build a nuclear plant on time and on budget. Does that mean rich people are barred from heaven or that nuclear plants are incapable of meeting their construction schedule? None of us knows the answer about the former just yet but history tells us the latter is well within the bounds of possibility.

However, with the new United States plan to stand up a fleet of eight AP1000s in partnership with Westinghouse and Brookfield, backed by an eighty billion dollar framework, that metaphor suddenly feels a lot less rhetorical and a lot more like a live policy problem.

We have a rare convergence in Washington. Biden framed nuclear as central to tripling clean electricity. The Trump administration has not only kept that direction, it has put much more political skin in the game, from explicit AP1000 fleet signals to hard cash for small modular reactors at TVA and Holtec.

For the first time since the early 2000s, there is real money, real political attention, and real load growth that actually needs firm power, from data centers and AI to electrification.

We have also been here before.

The last time the United States tried a nuclear renaissance, utilities created combined operating licenses, signed contracts with architect engineers, pushed AP1000 and ESBWR through design certification, and took on real nuclear construction risk. Then shale arrived, Vogtle and Summer spiraled, and the whole effort collapsed into a cautionary tale.

In a recent conversation with James Krellenstein, CEO of Alva Energy and one of the sharpest forensic minds in nuclear project history, we tried to answer a simple question:

What, concretely, has to be different this time so that eight AP1000s become the backbone of a real fleet, not the prologue to another lost decade?

What follows is my attempt to synthesize that discussion and tie it back to the broader Decouple project of understanding how large energy systems can get built in the messy contemporary reality of the Western World.

The World That Built Gen 2 Reactors

To understand why the classic American nuclear build worked when it did, you have to start with a utility structure that hardly exists any more.

For most of the twentieth century, United States power companies were vertically integrated, regulated monopolies. They owned generation, wires, and retail. They had defined geographic service territories, and they recovered both operating and capital costs directly from ratepayers, subject to prudence review by state public utility commissions.

Two features of that world matter for our story.

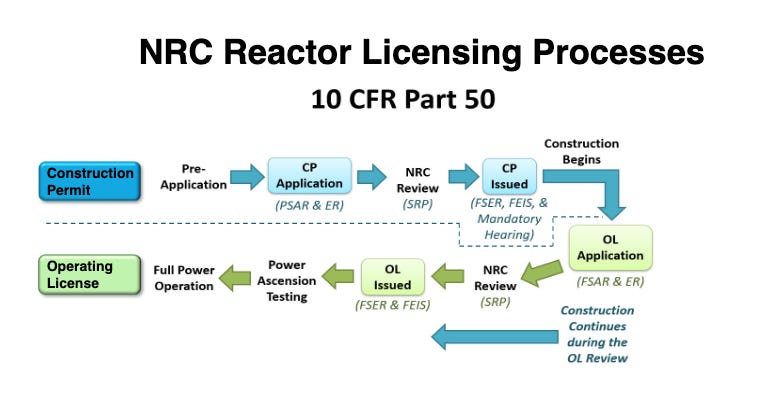

First, utilities were drowning in real work. In the 50’s and 60’s, electric demand in the United States doubled roughly every 8 years. That means, over a 24 year career, a utility engineer could see the system they inherited multiplied by a factor of eight. New coal plants, oil plants, hydro, transmission, everything.

Second, the regulatory compact paid them to build. Once a project was judged prudent, the capital went into rate base and earned an allowed rate of return, often on the order of ten to twelve percent. Utilities were being paid, in a regulated way, to mobilize capital and concrete.

Put those together and you get organizations that were absolutely saturated in project experience.

In that world, the way we structured nuclear looked strange, but it mostly worked. Westinghouse, GE, Babcock and Wilcox, and Combustion Engineering sold what they explicitly called nuclear steam supply systems, essentially nuclear boilers. Architect engineering firms like Bechtel, Stone and Webster, or Ebasco designed the balance of plant around that boiler.

The balance of plant, which is about half of the capital cost, was not standardized by the reactor vendor. There was no one integrated product called “a Westinghouse plant.” Sharon Harris, Beaver Valley, North Anna, and dozens of other Westinghouse units all married the same NSSS to different turbine islands, feedwater layouts, auxiliaries, and even containment designs, depending on which architect engineer the utility hired.

On paper, this sounds like a recipe for chaos. In practice, it worked because the owner organizations were so competent. Some utilities did not even bother with outside architects. Duke, for instance, engineered and managed most of its plants itself. Ontario Hydro did the same with CANDUs, at one point employing ten thousand people in its construction division alone, in what was jokingly described as a construction company that also happened to make electricity.

The key point is simple.

In the USA, nuclear was never a finished product sold out of a catalog. It was, and still is, a complex integration project, and the hardest part of that integration was done by the customer.

That model depended on utilities that were building plants constantly and could keep very large, very experienced project organizations together for decades. Which brings us to the first real rupture in the story.

Part 50, Part 52, And The Trauma Of The First Wave

The end of the Gen 2 build scarred the American utility industry in ways that are easy to forget from today’s vantage point.

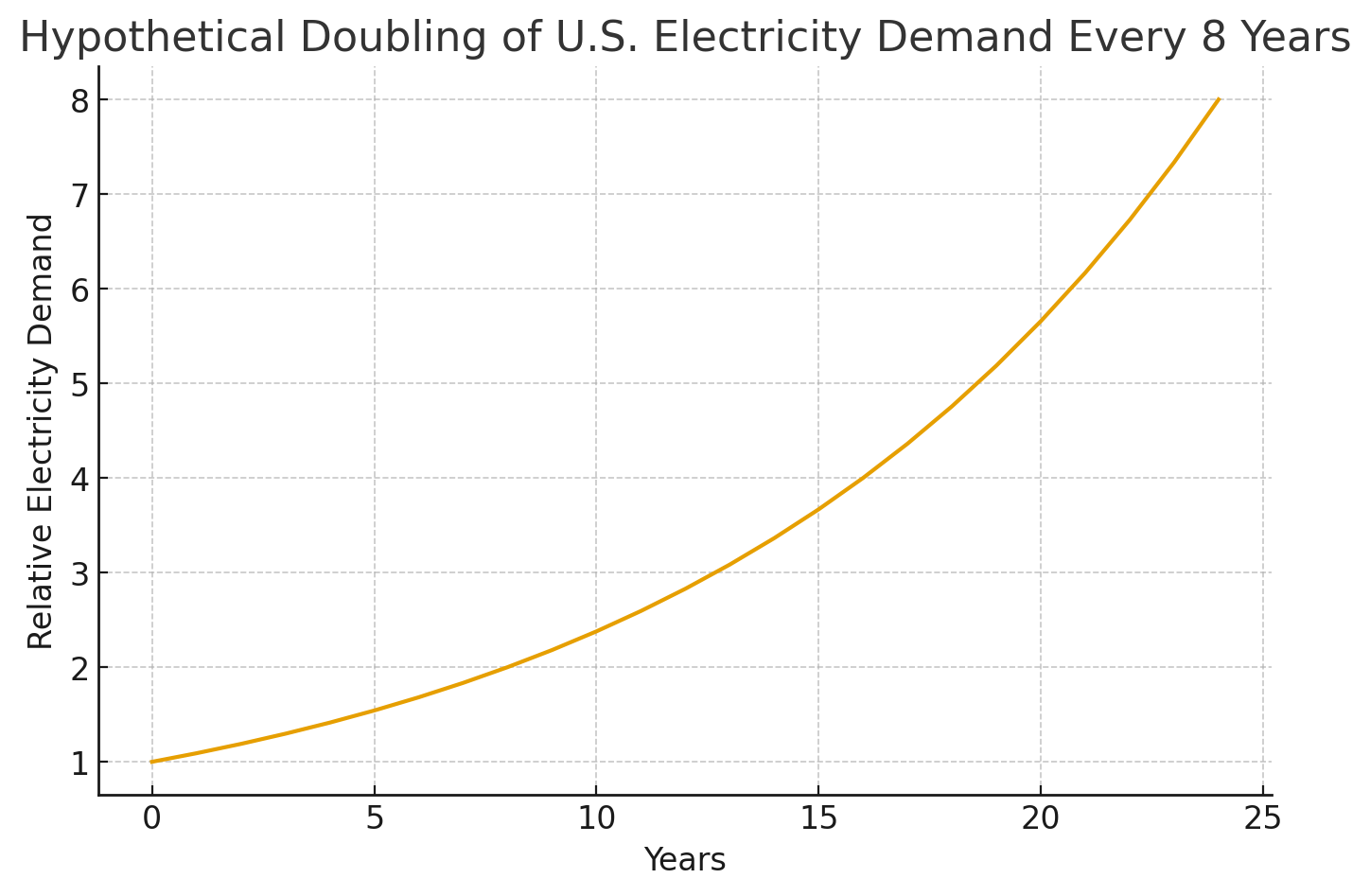

Under the old Part 50 two step licensing regime, utilities first received a construction permit, then, after billions of dollars had been spent, came back for an operating license. In between those two steps, the regulator changed the rules.

Plants that had been designed and partially built under one set of requirements suddenly had to comply with a new set of post Three Mile Island rules. Entire systems were ripped out and rebuilt. Sunk costs multiplied.

On top of that, there was a fatal political design flaw. Local governments could veto emergency plans that the NRC required for operation. Shoreham on Long Island was fully built, reached low power operation, then died because Mario Cuomo and Suffolk County refused to approve an evacuation plan. The cost was shoved onto Long Island ratepayers for decades. Seabrook came very close to the same fate.

You can see why utility executives swore never again.

Part 52, created in the late eighties, was the institutional response to that trauma. It introduced combined construction and operating licenses and design certifications. The idea was simple, get your design certified once, get a COL that incorporates that design and a specific site, build in accordance with that license, demonstrate via inspections, tests, analyses, and acceptance criteria that you did what you promised, and you are entitled to an operating letter without another round of regulatory re-litigation.

The NRC has never revoked a COL or refused a 103 g letter for a plant built as licensed. By that narrow metric, Part 52 works.

Part 52, however, was only one half of the attempt to de risk nuclear in the early two thousands. The other half was political and financial.

The Noughties Nuclear Renaissance Was A “Need To Have” Moment

If you zoom back to the early two thousands, the conditions that produced the last nuclear revival were very different from the ones we talk about today.

Natural gas was scarce and expensive. Henry Hub prices spiked above thirteen dollars per million BTU in the mid two thousands. The United States was a net energy importer, pursuing LNG import terminals and looking nervously at Middle Eastern supply.

You could not, politically or environmentally, build new coal without a fight. Air quality and respiratory disease were front page issues even before carbon entered the policy mainstream.

Then came 9 11 and the hard realization that the country had bound its economic security to a very unstable hydrocarbon nexus.

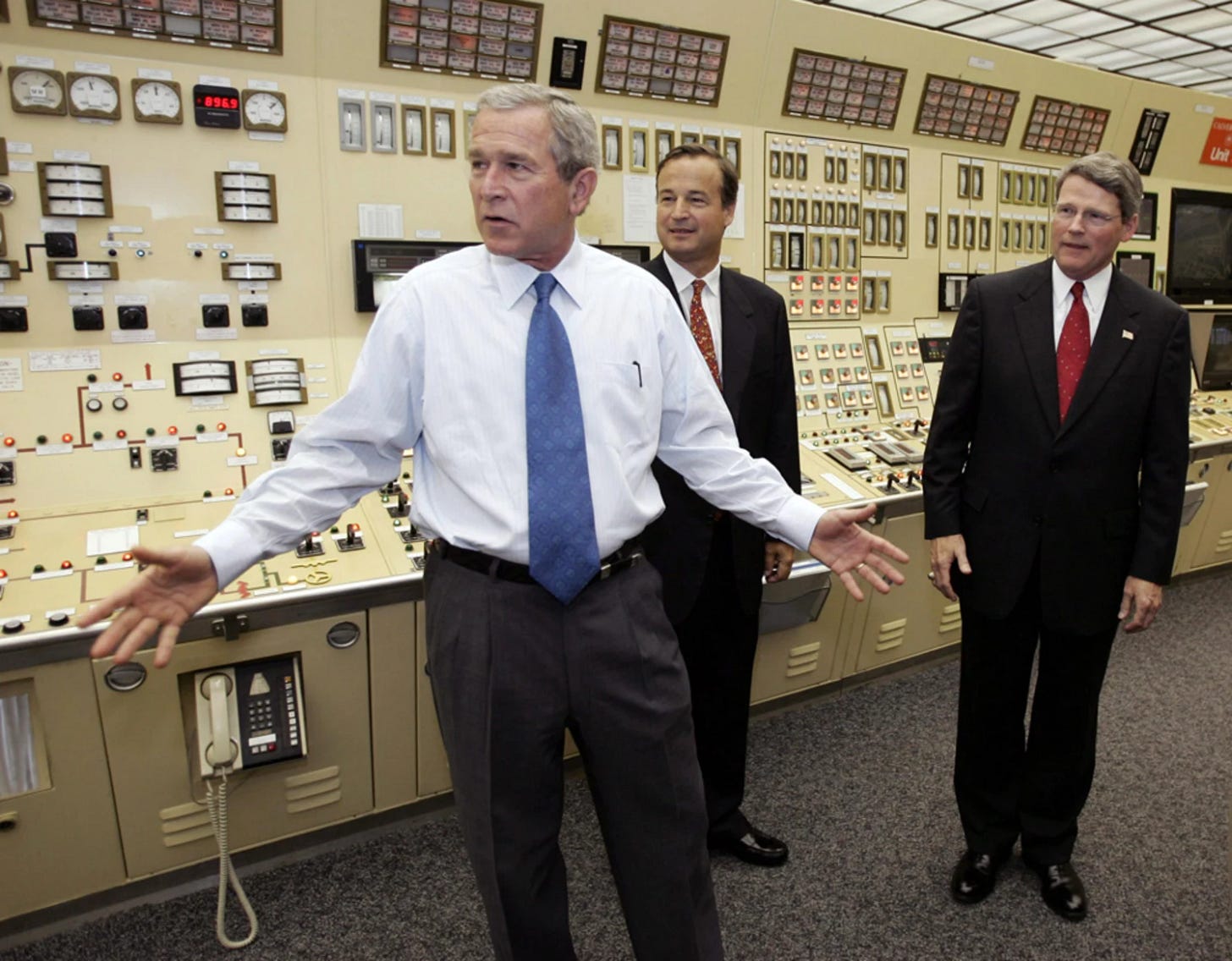

In June 2005, George W Bush flew to Calvert Cliffs in Maryland, the first presidential visit to a nuclear power plant since Jimmy Carter’s emergency trip to Three Mile Island in 1979. From the turbine hall he called for a new round of nuclear construction and urged Congress to pass a comprehensive energy bill that would later become the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which he ultimately signed that August at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico.

Nuclear in that world was not a green nice to have, it was a strategic need to have.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 encoded that logic. It created the DOE Loan Programs Office and gave it authority to provide loan guarantees that effectively let nuclear projects borrow at close to Treasury rates. It also provided production tax credits for the first movers, and it co funded the Nuclear Power 2010 and NuStart consortia that pushed AP1000 and ESBWR through design certification and early COL work.

Southern and its partners did not just talk about building reactors, they spent on the order of hundreds of millions to billions to secure COLs, begin site work, and place orders. Constellation and EDF pursued EPRs at Calvert Cliffs and Nine Mile Point. Toshiba arrived with ABWRs and the APWR. EPR applications showed up at Bell Bend and in Pennsylvania. This was not a vendor side marketing exercise. It was utility led and utility financed, often in regulated states that could put licensing costs into rate base and earn a return.

And yet it failed.

What killed it was not a lack of subsidies or a lack of designs. It was the combination of shale, institutional memory loss, and an owner side capacity problem that Part 52 simply did not touch.

Shale, Vogtle, And The Collapse Of Confidence

The shale revolution flipped the economic table.

Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing in shale formations produced a flood of domestic gas. Power markets that had assumed scarce and volatile gas suddenly saw abundant cheap fuel. Coal plants were retired en masse because combined cycle gas plants were simply cheaper to build and run, even before environmental rules pushed in the same direction.

In that environment, the question in many boardrooms became brutally simple. Do we spend ten years and billions of dollars building two gigawatts of nuclear with enormous construction risk and national scrutiny, or do we quietly build a couple of gas plants outside town and be done in three years?

Fukushima did not help. Public support dipped, and the optics were terrible. But as James points out, the technical analyses that followed Fukushima actually strengthened the case for the Gen-3+ designs in the U.S. pipeline. Both the AP1000 and ESBWR were shown to be specifically not vulnerable to the kind of prolonged station blackout that destroyed Fukushima Daiichi, because their passive safety systems could maintain core cooling and containment integrity for days without AC power or operator action. (see our earlier episode with James below for a deep dive of the AP1000 safety systems)

The NRC incorporated these findings, paused briefly, then issued every U.S. COL for Gen-3+ reactors after Fukushima. The regulatory process moved forward because the designs addressed the very failure mode under scrutiny.

The real killer was not regulatory, it was economic.

Then Vogtle and Summer made everything worse by demonstrating, in real time, that the American supply chain and project culture had lost the muscle memory needed to build a large light water reactor.

Modularization was supposed to be the solution. Instead, it magnified inexperience. Chicago Bridge and Iron, with oil and gas fabrication heritage, struggled to deliver nuclear quality modules. Quality assurance was weak. At one point, core makeup tanks had to be shipped back to Italy because they had been fabricated to the wrong volume. A developer with a strong owner side organization might have caught that in the shop. Instead, it was caught on site, with all the schedule consequences that implies.

SCANA executives ended up in jail over the Summer fiasco. Southern’s balance sheet was battered by Vogtle. Utilities executives took the lesson that nuclear risk was potentially career ending, even when underpinned by federal loan guarantees and state level cost recovery laws.

By the time shale was in full swing, the Noughties renaissance was finished.

Which brings us to today.

The 2025 Moment Looks Better On Paper

On paper, the policy environment for new nuclear in 2025 is stronger than anything we saw in 2005.

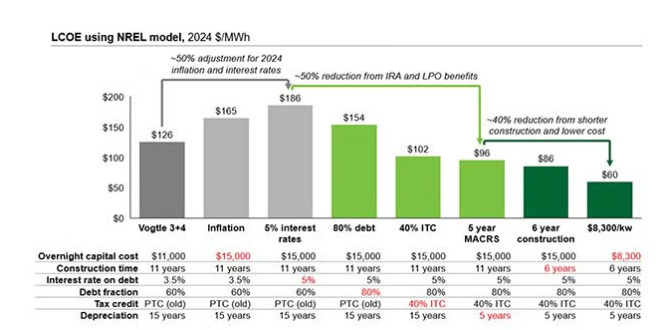

The Inflation Reduction Act created a technology neutral clean electricity ITC and PTC that nuclear can use. Existing plants get a production credit that keeps them competitive against cheap gas and subsidized renewables. New plants can access an investment tax credit of thirty percent, with ten percent adders for things like domestic content and energy communities.

The DOE Loan Programs Office has been scaled up and proven. It provided twelve billion dollars in loan guarantees to Vogtle that are being repaid, and it is now supplying up to 1.52 billion to support the restart of Palisades, with multiple disbursements already out the door.

On the small reactor front, the Department of Energy has just committed up to eight hundred million dollars in cost shared funding to TVA and Holtec to advance BWRX 300 at Clinch River and SMR 300 units at Palisades, on top of the Palisades restart loan. TerraPower’s Natrium demonstration has cleared the NRC’s final safety evaluation for its Kemmerer construction permit.

Load growth is no longer an abstract climate model. Data centers for artificial intelligence and cloud services, electrified vehicles, and heat pumps are all real and visibly straining grids. That demand is already showing up in integrated resource plans and capacity auctions.

Politically, this is one of the few areas of genuine continuity across administrations. Both parties now talk about tripling or quadrupling nuclear capacity in the same breath as they talk about semiconductors, critical minerals, and strategic rivalry.

For the AP1000 specifically, the new United States Japan alliance around large reactors, the Polish program, and the eight unit fleet concept in the United States are finally starting to look like the kind of standardized program that AP1000 needed all along.

So why does it still feel like we could absolutely blow it?

Because one core variable that the policy debate largely ignores is still missing, and that is the existence of robust developer organizations that sit between vendors and utilities and actually know how to deliver a fleet of plants.

The Case Control Study From Hell: St Lucie 2 Versus WooPPSS

James likes to use a simple question to test our theories of project success.

If the hardware, the vendor, the design, and the regulator are all the same, why do some plants come in more or less on time and budget while others become municipal bond disasters?

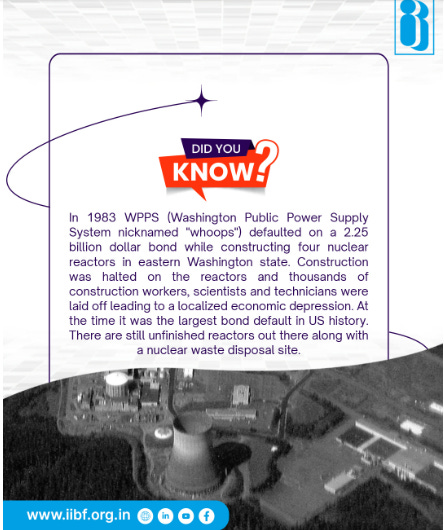

His favorite case control pair is St Lucie Unit 2 in Florida and Washington Nuclear Project 3 in Washington State, both combustion engineering reactors with Ebasco as architect engineer, both under the NRC, both starting in the same era.

St Lucie 2 is one of the quiet success stories of American nuclear. It went from nuclear construction to cold hydro in about five years, post Three Mile Island, with the NRC in full flight. It was built by Florida Power and Light working in a hybrid organization with Ebasco. FPL stood up a couple of hundred person internal projects org whose only job was to deliver new nuclear for FPL, and it rode herd on its contractors.

Washington Nuclear Project 3, by contrast, helped trigger the largest municipal bond default in American history at the time. The Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS) was a loose consortium of dozens of small public utilities that had never built large thermal plants before. The developer org simply did not exist.

The timing was the same. The hardware was the same. The vendor was the same. The regulator was the same. The difference was the owner side organization that integrated, supervised, and disciplined the work.

You see the same pattern elsewhere. Costs fell significantly between Palo Verde 1 and Palo Verde 3 as Arizona Public Service learned and improved across three standardized units. Then that projects organization never built another plant. This stands in sharp contrast to France, where EDF acted as a national developer that kept one projects organization together across dozens of standardized units.

In North America today, the closest thing we have to that EDF model is Bruce Power and Ontario Power Generation. The sequence of life extension refurbishments at Bruce A and B, with power uprates layered in, is training an integrated projects organization that can slide directly into building the four large reactors planned for Bruce C. The technology forces a heavy mid life rebuild, which in turn keeps a competent construction org warm.

The blunt lesson is this, nuclear build success is more tightly correlated with the quality of the owner or developer org than with the reactor vendor or even the regulator.

And that is exactly the variable that is weakest in the United States right now.

Our Owner Organizations Are Weaker Than They Were In 2005

It is uncomfortable to admit, but the institutional position of American nuclear is in some ways worse than it was at the start of the Noughties renaissance and dramatically worse compared to the heydays of the 1960’s.

The last new large plant to reach commercial operation before Vogtle was started in the seventies. In the decades since, many utilities simply shut down their nuclear fleets, sold their plants to specialist decommissioners, or cut their nuclear divisions to the bone to survive in competitive markets against cheap gas. That hollowed out project organizations and capital project departments.

The people who used to do major turbine replacements, uprates, and life extensions retired or moved on.

Even where pioneering work has been done, as with Bechtel and SGT driving steam generator replacement outages down from eighteen months to under a month by getting very good at procurement and outage choreography, that expertise is siloed into a handful of contractors and client teams, not spread across a big build program.

On top of that, the psychological trauma of Summer and the cost and schedule drama at Vogtle sit on every utility board’s mind. SCANA does not exist any more. Southern survived, but every executive in the industry knows what happened there.

When Jigar Shah at the Loan Programs Office asks, as he has, why utilities are not lining up to claim “candy bar” loan guarantees for new AP1000s, this is the answer. It is not that the candy is fake. It is that nobody wants to be the next CEO whose face is in every trial exhibit.

This is why the fashionable idea of “cost overrun insurance” is at best incomplete and at worst dangerous.

The Mirage Of Cost Overrun Insurance

You hear a simple story. Nuclear is scary because of cost risk. Therefore the government should create a pot of money that covers, say, the first twenty five or fifty percent of cost overruns, and suddenly cautious utilities will be willing to play.

The problem is that insurance is not magic, it is incentives.

If the people who can spend extra hours and extra materials know that part of the extra bill will be picked up by someone else, the incentive to control costs weakens. For EPC firms in particular, “overruns” are also additional billable work. For an owner side organization that is already underpowered, external insurance can quietly become a way of outsourcing cost discipline to Washington.

You can see how deeply this incentive rot ran in late Gen 2. James described at least one case where a project manager delivered an entire nuclear project on time and on budget, only to be reprimanded by his superiors. Because regulated utilities earned a return on “prudent” capital additions, delay, redesign, and rework actually increased earnings. Finishing efficiently reduced the rate base. In that environment, a manager who tried to run a disciplined project was punished for doing exactly what the public assumed a utility wanted to achieve.

And the way many utilities maintained that distorted incentive structure was by using the NRC itself as a shield. In the late Gen-2 prudence hearings, the cleanest way to ensure that overruns would be ruled prudent and therefore rate-base eligible was to demonstrate that the cost increase flowed from an NRC requirement, inspection finding, or licensing change. That dynamic created a subtle but powerful incentive for builders and owners to welcome regulatory churn, or at least not resist it too hard, because the more the NRC intervened, the easier it became to socialize overruns onto ratepayers rather than shareholders. The regulator, intended as a safety watchdog, became an unwitting guarantor of cost recovery.

Cost overrun insurance that is not paired with a very strong owner side project organization risks recreating this exact moral hazard, only with Washington paying the bill instead of ratepayers.

Which brings us back to what needs to change.

What It Would Take To Thread The Needle This Time

If we really want eight AP1000s to be the backbone of a real fleet program, three things have to happen in parallel.

1. Build Developer Organizations Before You Build New Reactors

The most important thing missing from the United States nuclear landscape is not another design, it is credible developer orgs that can demonstrate they know how to deliver nuclear megawatts.

There is a reason Alva Energy, the company James leads, is focused first on power upgrades and life extension projects, not jumping straight to a first of a kind new build. There is a reason Bruce Power is sequencing refurbishments before Bruce C. These projects are large enough to test and train an organization, but small enough that failure does not take down a utility.

The United States has gigawatts of latent nuclear capacity locked up in uprates, refurbishments, and restarts. Palisades is the first restart of a shuttered commercial reactor in American history, backed by a 1.52 billion dollar loan guarantee, and fuel has already returned to site. Getting that right is not just about one plant in Michigan. It is about demonstrating that our ecosystem can still do complex nuclear work, on schedule, under regulatory scrutiny.

A rational AP1000 program would consciously cultivate one or more developer orgs through a pipeline of such projects, then hand them the responsibility for delivering a four unit site in partnership with a host utility.

2. Create Offtake Structures That Can Carry The First Projects

The first few AP1000s in a new program are almost guaranteed to be more expensive than the eighth. There will be learning, there will be process improvements, there will be conservative contingencies.

The only way that is financeable is if there is a counterparty with rock solid credit that is prepared to sign up for a power price high enough to support those contingencies. That might be a state backed entity like NYSERDA, aggregating load on behalf of multiple buyers. It might be an anchor offtake from a cluster of data centers that need credible decarbonized power in a world where grid upgrades and new gas permitting are both hard.

What it cannot be is a merchant bet where the entire economics of a plant live and die on the PJM day ahead price.

One useful piece of continuity from the Biden era is the explicit recognition, in DOE’s 800 million dollar SMR awards, that cost shared grants for early projects are justified as a way to unlock later fleet deployments. (The Department of Energy’s Energy.gov) That logic should apply even more strongly to large standardized units.

3. Do Smart Advanced Procurement Without Repeating Vogtle

The instinct to place long lead orders early is right. Reactor pressure vessels, steam generators, and other heavy forgings have long manufacturing times. In theory, warehousing components for eight units should let you move quickly once sites and developers are ready.

There are two big caveats.

The first is quality assurance. Ordering eight sets of core makeup tanks from Europe or Asia does you no good if someone discovers years after warehousing these parts that the volume is wrong when they arrive on the construction site. Actual nuclear projects that go well, from steam generator replacements to major component swaps, do not trust paperwork alone. They put owner representatives in the forge and the shop, measuring, witnessing welds, and checking test records.

If advanced procurement is run as a remote federal program, decoupled from the owner orgs that will actually use the kit, we will be setting ourselves up to repeat Vogtle’s mistakes at scale.

The second is supply chain realism. The United States no longer has indigenous capability to forge and assemble large reactor pressure vessels and steam generator shells at nuclear quality. That work is currently done in allied countries, at places like Doosan in South Korea or Le Creusot in France.

We should not wait for a fully domestic forging industry before placing AP1000 orders. The United States originally seeded those capabilities through technology transfer. Westinghouse co founded Framatome, whose very name, French American Atomic Constructors, tells the story. Combustion Engineering provided the basis for the Korean System 80 lineage. Now the flow can run in reverse.

A sensible policy might explicitly waive tariffs for the first few sets of heavy components to get projects moving, then phase in domestic content requirements over time, paired with IRA domestic content tax credit adders. That is how you signal to industry that the demand is real enough to justify rebuilding forge capacity onshore without using domestic manufacturing as a pretext for yet more delay.

The SMR Sideshow, And Why Big Reactors Still Matter

None of this is to dismiss the genuine progress on the small side.

TVA’s BWRX 300 at Clinch River has federal cost share backing and a direct line to an operating utility that still knows how to run nuclear. Holtec’s SMR 300 will piggyback on Palisades restart work and, if it goes ahead, will effectively make that site a mixed fleet campus. TerraPower’s Natrium is pushing the regulatory envelope for advanced reactors at Kemmerer.

These are real projects now, not just glossy renderings.

The danger is that SMRs become a distraction or psychological excuse to avoid the hard questions about how to build large standardized plants, on which any serious reindustrialization agenda will depend. The grid needs big, cheap megawatts at scale, and once you get past first of a kind novelty, the economy of scale of large light water reactors still rules the day.

If we treat SMRs as a training ground for project organizations and as a diversification of the portfolio, they could be valuable. If we treat them as a way to avoid ever building another gigawatt class plant, we have learned the wrong lesson.

Learning From History Without Being Crushed By It

The most depressing way to read the history of the American nuclear industry is as a story of repetition, where every attempt at revival is swallowed by the same combination of cost overruns, regulatory churn, and cheap gas.

This is not inevitable.

Part 52 has fixed one of the worst structural problems of the Part 50 era. The Loan Programs Office has shown it can deploy low cost capital and get it paid back. The Inflation Reduction Act has quietly leveled the playing field for nuclear against subsidized wind and solar. Shale has done most of the retirement it is going to do.

The real question now is organizational.

Can we build and sustain developer organizations that are rewarded for delivering, not just for announcing? Can we structure early projects so that utilities are not betting the company, but are still sufficiently on the hook to care deeply about schedule and quality? Can we resist the temptation to imagine that choosing the right reactor design is the decisive variable, when every historical comparison shows that outcomes hinge on the strength of the developer organization rather than the product itself?

If we can do those things, eight AP1000s will not be a moonshot, it could even be a starting point.

If we cannot, all the loan guarantees, tax credits, and presidential speeches in the world will not stop us from pulling defeat from the jaws of victory, again.

The camel and the needle image can be read in two ways.

One reading says nuclear construction is impossible and we are fools to try. The other, more accurate reading is that the obstacle is not the needle, it is the size and shape of the institutions trying to pass through it. If we reshape those institutions, the passage becomes difficult but no longer impossible.

The second nuclear renaissance will only be real if we approach institutional design with the same seriousness that engineers applied to the AP1000’s passive safety systems.

If you value this kind of deep dive into the unglamorous mechanics of how energy systems are actually built, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to Decouple, sharing this piece with a friend, or supporting our work through a donation. Independent, technically grounded analysis only happens when there is an audience willing to back it.