Ken Petrunik: A Case Study of Excellence from Canada’s Nuclear Golden Age

In this special episode, I sat down with someone whose name should be far better known in Canada and beyond. Ken Petrunik belongs to a small cohort of leaders who carried real responsibility for some of the most complex construction projects Canada ever undertook, and who helped establish Canada as a serious nuclear nation during the period when it actually built reactors at scale.

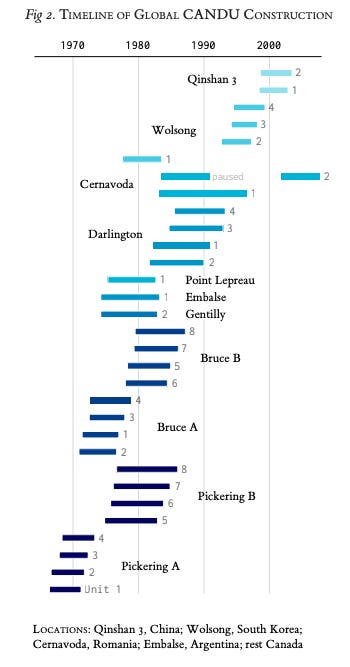

Petrunik was formed during the peak decades of Canada’s nuclear build program, when thirty five large CANDU reactors were constructed domestically and internationally over roughly thirty years, including periods when as many as ten units were under simultaneous construction.

The system that trained him was demanding and often unforgiving and operationally decisive. Responsibility attached to individuals rather than processes, and decisions were made by people who would later have to live with their consequences, sometimes for decades. That environment shaped a generation of project managers capable of integrating engineering reality, political pressure, labor dynamics, and schedule risk into a single operational picture.

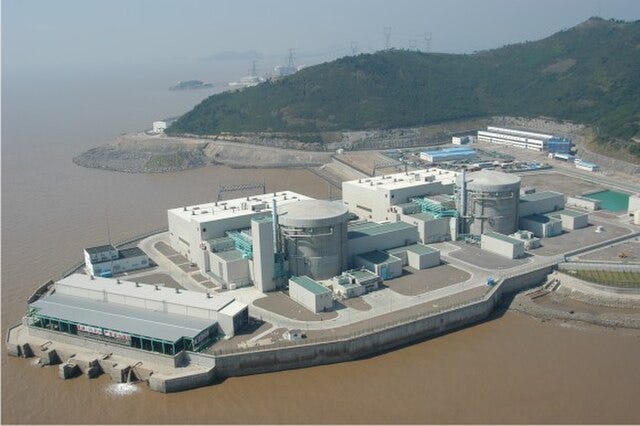

That trajectory culminated in Petrunik leading the last CANDU reactors completed as true greenfield new builds, the Qinshan Phase III units in China, which were delivered ahead of schedule and under budget under a high risk fixed price engineering, procurement, and construction contract. Outcomes of that kind remain rare in nuclear construction because they require accumulated delivery capability and they depend on decisions taken early by people who understand how construction failures propagate before they become visible.

Standing on the shoulders of giants. Time to look down

As Canada once again contemplates an ambitious domestic buildout of large nuclear power, and as relations with China cautiously re warm alongside renewed export ambitions, there is urgency in studying the people who led a world class industry while that knowledge still exists. Contemporary nuclear debates devote enormous attention to reactor concepts, licensing philosophies, and steam supply system variants, while paying far less attention to the human factors constraints that determine whether any of those designs ever become operating plants. Nuclear success has always depended on a small number of project managers capable of holding technical complexity, institutional friction, and political pressure in balance while moving a project forward in real time.

Ken Petrunik’s career helps explain why some reactors arrived early and others never did. It functions as a case study in the flourishing, and eventual erosion, of nuclear build capability across time, geography, and political change.

Formed in the Only Environment That Could Produce Him

Petrunik’s development cannot be separated from the institutional environment in which it occurred. He joined Atomic Energy of Canada Limited when AECL functioned as a national design authority embedded in an active construction program, rather than as an advisory body removed from execution, and when Ontario Hydro was adding large baseload capacity at a pace that sustained continuous learning across design, construction, commissioning, and operations. Canadian suppliers were not acquiring nuclear grade capability through demonstration projects or paper qualification, but by manufacturing components repeatedly under real delivery schedules.

This environment produced professionals who accumulated full cycle exposure. Engineers and project managers moved between design offices, construction sites, commissioning teams, and operating stations, developing an intuitive understanding of how drawings translated into pours, how procurement delays constrained labor productivity, and how regulatory sequencing interacted with construction reality. Petrunik’s own background reflects this integration, combining technical grounding in reactor thermal hydraulics with extended periods living on site, where the relationship between planning and execution could not be abstracted away.

That exposure shaped how he approached project control, keeping attention on the small set of actions that genuinely governed progress rather than on accumulating layers of process. Living with the downstream consequences of procurement delays, interface mismatches, and sequencing errors produced a concrete sense of timing and priority. The system that formed Petrunik reinforced this discipline through repeated engagement with live projects, embedding judgment through experience long before later governance frameworks attempted to substitute procedural complexity for firsthand knowledge of how builds actually fail.

Exporting CANDU as an Execution System

Canada’s success exporting CANDU reactors is often attributed to the technical attributes of the design, including fuel flexibility, heavy water moderation, and natural uranium economics, all of which contributed to competitiveness in specific markets. Those features alone, however, do not explain why Canadian projects survived political instability, institutional disruption, and financing uncertainty that would normally undermine nuclear construction.

What accompanied the reactor hardware was an execution system that treated the owner and vendor as a single delivery organism rather than as counterparties attempting to shift contractural risk.

Qinshan and the Logic of Early Decisions

The Qinshan Phase III project provides the clearest window into Petrunik’s approach to nuclear construction. The contract imposed a compressed schedule with minimal tolerance for learning during execution, while labor quality uncertainty and political visibility amplified the cost of delay without expanding tolerance for failure. Under these conditions, recovery depended on decisions taken before their necessity was obvious.

One of the most consequential choices involved adopting open top construction, leaving the reactor building open longer than conventional practice to permit installation of large components by crane. Although the approach had been discussed on earlier CANDU projects, it had not previously been implemented, in part because it introduced civil engineering unknowns and required confidence that benefits would materialize later rather than immediately. The decision imposed near term difficulty in exchange for latent resilience.

Years afterward, when steam generator fabrication problems emerged, that earlier choice prevented what would otherwise have become a schedule failure, because installation flexibility had been preserved before the constraint was visible. The benefit existed only because the decision had been made early, by someone who understood the entire build sequence and could visualize how downstream failure modes would interact with structural choices made at the outset.

At Qinshan, one of the most high stakes moments came during a critical concrete pour on the reactor building compound containment when the 24 day continuous slip-forming operation began to fail in the middle of the night. The concrete was already moving, the formwork was under stress, and stopping the pour would have introduced cold joints that could have compromised structural integrity and schedule.

Rather than escalating the issue up a distant management chain or pausing for procedural clarity, the response was immediate. The team shifted to manual bucket placement, kept the concrete workable, maintained continuity through the night, and stabilized the pour until the formwork system could be restored by morning. The episode captures a defining feature of the project’s success, namely that authority, technical judgment, and accountability were present on site at the moment of failure, allowing a potentially schedule-breaking event to be absorbed through decisive action rather than converted into a prolonged disruption.

Throughout the project, Petrunik insisted that the owner see the real schedule drivers rather than a sea of minor tasks. The focus stayed on the few activities that could actually delay the plant, which made it easier to make decisions quickly when problems appeared. Because both sides were looking at the same risks, effort went into getting the project back on track instead of arguing about who was at fault. The project stayed manageable because despite surprises occurring, they were identified early and handled by people with the authority to act decisively.

Why Software Was Not a Magic Bullet

Across his career, Petrunik watched successive waves of project management software arrive with the promise that greater control could be achieved by breaking work into finer and finer pieces. Schedules expanded from a few thousand activities to hundreds of thousands, driven by the belief that more detail and more data would translate into better predictability. In practice, the growing volume of information often made it harder to see the small number of constraints that actually determined whether the project would finish on time.

As schedules and reporting systems became denser, senior leadership found it increasingly difficult to separate what truly mattered from what merely existed on paper. Construction, meanwhile, continued to advance according to physical realities that no amount of planning sophistication could override, including crane access, concrete cure times, labor coordination, sequencing conflicts, and tight spatial tolerances. Tools designed to demonstrate completeness and progress gradually redirected attention away from decision critical risks and toward the maintenance of elaborate representations of the project.

Petrunik deliberately resisted this drift by keeping the control schedule at a level that supported real decisions. Detail was added only when a specific problem demanded it, allowing the critical path to remain understandable and actionable. The underlying judgment was simple and hard won, namely that distance from the work, even when mediated through highly detailed tools, weakens decision making rather than strengthening it, and that execution improves only when tools reinforce direct understanding of how the job is actually being built.

The Loss of the Builder Environment

By the later stages of Petrunik’s career, the Canadian environment that had produced him no longer existed. A prolonged plateau in electricity demand removed the system level justification for continued baseload expansion, and once the need to keep building disappeared, the institutions that sustained delivery began to decay. Construction cadence slowed, feedback loops lengthened, and experiential knowledge stopped accumulating across generations.

Atomic Energy of Canada Limited was dismantled as export prospects receded, while Ontario Hydro was restructured around asset management rather than expansion. Greenfield construction gave way to refurbishment programs that preserved isolated technical skills without reproducing the integrated builder ecosystem that had once linked design, construction, commissioning, and operations under continuous schedule pressure. New entrants encountered a sector increasingly oriented toward analysis, licensing, and risk management, with limited opportunity to experience full project delivery.

Western nuclear programs now attempt to restart construction without a generation that has built at scale, compensating by importing governance frameworks, expanding oversight, and placing hope in novel reactor concepts or digital systems. These responses address symptoms rather than the underlying loss of experiential capacity. Petrunik’s later work in the Middle East underscores the contrast, as countries establishing nuclear programs prioritize recruiting individuals with demonstrated delivery experience and organizing institutions around their authority.

What Canada Is Deciding Now

The significance of Petrunik’s career lies in what it reveals about how nuclear capability is formed and lost. Builder competence is the result of sustained exposure to projects that require decisions to be made under pressure. Continuity matters because it creates repeated opportunities to exercise judgment, observe failure modes, and internalize how recovery actually occurs.

Canada’s re-entry into nuclear construction through small modular reactor projects at Darlington is occurring within a project management culture shaped by contemporary Western governance norms, where authority is diffuse, oversight is layered, and risk is carefully distributed away from individual decision makers.

The question Canada now faces is whether it is prepared to recreate the conditions under which that capability emerged previously, including concentrated authority, accountable decision making, and continuous exposure to delivery under real schedule pressure. Nuclear plants that arrive on time reflect choices about how people are trained, how authority is exercised, and how consequence is assigned. Canada once created these opportunities. The current build cycle will reveal whether it is able to do so again.

Resources:

Ken Petrunik: Practical Project Management. https://books.google.ca/books?id=D40ZCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

CANTeach Construction of CANDU in China: A success story. https://canteach.candu.org/Content%20Library/20031901.pdf