Welcome back to Decouple, the best source for cutting edge analysis on nuclear energy, with weekly interviews by Chris Keefer. Watch on YouTube, Spotify, or Apple.

This week I sit back down with François Morin in his third appearance on the show. François is the World Nuclear Association’s point person on China. He works and travels inside China, speaks fluent Mandarin, and spends time at the conventional and advnaced reactor sites that the rest of us argue about on Twitter. He also has an unusually candid view, a welcome antidote to the hype so prevalent in the West at the moment.

We cover how quickly China is really building nuclear power compared to highest water mark of the French Mesmer plan, how that compares to Chinese coal and gas deployment, why Chinese nuclear is still almost exclusively coastal, and the use case, build times and performance of the so-called advanced reactors that Western startups are currently pitching to investors.

Watch the full conversation on YouTube:

We talk about

How many reactors China is actually building per year and why that still only gets them to about 5 percent of national electricity.

The quiet but very real bottleneck: the nuclear safety regulator.

Why China is still building roughly 90 gigawatts of coal compared to only 7 gigawatts of nuclear per year.

China’s plans for a massive natural gas expansion.

Siting limits: why almost all Chinese nuclear is on the coast and why inland builds are still politically toxic.

Reality check on the scale and scope of the Chinese fast reactor, high temperature gas reactor, molten salt reactor, and the ACP100 an integral PWR small modular reactor programs.

What this implies for Western advanced reactor companies promising commercial plants before 2030.

Deeper Dive

“You have 10 reactors per year authorized at the state council level, but only half of them start real construction. The reason for that is the safety authority which says something about Chinese institutions.”

China is building nuclear. Just not at the mythical pace people imagine. From the outside, the narrative often goes like this: China can just decide to build nuclear power, point at a map, and drop 20 new plants.

François tells a different story.

Yes, China is building. The country has roughly 61 gigawatts operating today, roughly 37 gigawatts under construction, and is on track to pass total United States nuclear capacity around 2030. That is a historic milestone.

But zoom out. Nuclear is still stuck at about 5 percent of Chinese electricity generation, a far cry from 18% in the USA and 65% in France. Whether you sample the last few years at 4.7, 4.9, or 5.0 percent, the needle barely moves. The state has floated rhetorical targets of 15 percent nuclear by 2035. François is blunt: there is no plausible way they get there.

Why not. Two reasons.

First, the safety regulator. We tend to caricature Chinese regulators as rubber stamps. According to François, that is not how it works. Beijing can approve 10 new units at the State Council level in a given year. Only about half of those actually move forward in any given year. The other half sit, sometimes for a long time, while the nuclear safety authority grinds through site specific review. In other words, even in China the regulators can slow down the almighty Chinese Communist Party dictates.

Second, unlike 1970’s OPEC shocked France with no significant fossil fuel resources to tap the Chinese have abundant coal, renewables and plans for a massive build out of gas capacity. In 2024 China reportedly began construction on roughly 7 gigawatts of new nuclear. Sounds huge compared to the West. In the same window, China began 94 plus gigawatts of new coal construction. That ratio matters.

China will very likely keep pouring first concrete for roughly five reactors per year. If they simply hold that pace, François says they could plausibly get to something like 200 gigawatts of nuclear capacity by around 2040. That is gigantic by global standards. It is still not civilization changing inside China.

Natural gas, not just solar panels, is the big story. Western climate conversation tends to frame Chinese energy policy as coal on the way out, wind and solar on the way in, and nuclear as the clean firm backbone.

François walks through a different math. Chinese planners expect a huge increase in electricity demand between now and 2030 from two sources that barely existed a decade ago: electric vehicles and data centers. He estimates that just these two loads together could require the output of on the order of forty full scale nuclear plants by 2030.

Where will that come from.

Not just nuclear, which is adding new units but at a measured pace.

A significant contribution will come from wind and solar.

But the biggest surprise for me was: natural gas.

China already produces something like forty to forty five percent of its natural gas domestically and is increasing that output by mid single digits per year. It also imports pipeline gas from Central Asia and Russia and LNG by ship from everywhere from Qatar to Australia. The new contracts for additional Russian pipeline gas get a lot of headlines, but Russia still accounts for only twenty percent of Chinese gas imports. In other words, China is not betting its grid solely on Gazprom.

François puts a striking figure on it. The expected ramp in gas consumption through 2030 is equivalent to the output of roughly one hundred twenty plus nuclear reactors. Gas is the flexible, dispatchable, politically acceptable bridge for new load like AI data centers. Nuclear is important, but it will not replace most of that gas on the timeline that matters.

Coastal siting is now a hard physical limit. Almost all of China’s nuclear fleet sits on the coast. This is not just about seawater cooling convenience. It is about fear of river floods.

Chinese political culture still carries deep memories of catastrophic inland flooding, with disasters on the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers that killed hundreds of thousands to millions of people in the twentieth century. In fact flood control and hydrological engineering is perhaps what lies at the heart of historical Chinese statehood, as one of the emperor’s core duties. That mentality is still alive inside modern institutions.

After Fukushima, that inherited fear found a modern shape. Officials and local stakeholders worry that if a nuclear plant on a major inland river floods, contamination would be carried downstream and render agricultural water unusable. François notes that this is not really a health physics argument. It is a social and political one. You can see the same instinct in China’s harsh (and scientifically unjustified) criticism of Japan’s release of treated Fukushima water, which contained on the order of a gram of tritium in a million tons of water. The outrage was not scientific. It was political and emotional.

In practical terms, this psychology has throttled inland nuclear. Beijing has advocates who loudly argue that China must never build reactors inland and should instead rely on renewables. So even though there is still cooling water available on major rivers, there is a political wall around using it for nuclear power.

That creates a new constraint. The big coastal sites are filling up. Some have six units. Some are planned for eight or nine. François mentions Tianwan as a site heading toward roughly eight units, and others with similar clustering. You can only do that so many times along the coastline. Past roughly 190 gigawatts of coastal capacity, using current sized units, China starts running out of good waterfront.

China has two options if it wants to go beyond that ceiling:

Move inland and win that political fight around flood risk and water releases.

Make each coastal site produce more megawatts per reactor by moving to “extra-large modular reactors.

That second path is already visible.

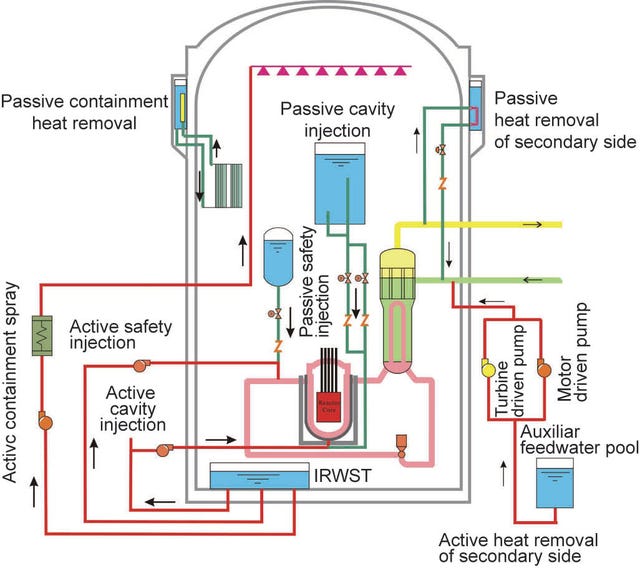

Standardization, Hualong and the Chinese AP1000, and the slow move to bigger cores. Twenty years ago, China sampled the global reactor buffet: French PWRs, Canadian heavy water reactors, Russian VVERs, U.S. AP1000s. The goal was to learn from everybody. That era is ending. The long term fleet is converging on two large China-fied designs.

Hualong One, a Chinese Generation III plus pressurized water reactor derived in part from French technology.

CAP1000 and its scaled up cousin CAP1400, Chinese builds based on the AP1000 line.

Both families use modern passive safety features. Gravity fed emergency cooling water, hardened backup power and digital controls. Both are considered Gen III plus. In practice, though, the build pipeline is tilting toward Hualong. François counts only a handful of Hualong units already connected, another eleven under construction, and roughly forty plus in planning. The CAP1000 and CAP1400 line is still active, but the numbers are slightly lower.

There is a quiet strategic reason for the CAP1400. It is a power uprate. A CAP1400 class unit gives more output per licensed coastal site. That being said, François notes that State Power Investment Corporation originally talked about six CAP1400 units at one new site but when they finally pulled permits this year they started with two CAP1000 units instead. In other words, the 1400 class looks promising on paper, and one early CAP1400 has achieved something like a five year construction schedule, but the supply chain and regulator are not ready to mass replicate it yet. That will take time.

Still, the direction of travel seems clear. Larger single unit output is how you squeeze more gigawatts out of scarce approved seaside plots.

Advanced reactors in China: what is really working and what is not

In North America and Europe, fast reactor startups, high temperature gas reactor startups, molten salt reactor startups, and compact SMR startups are raising money at multi billion dollar valuations. Some are promising electricity sales in 2027 or 2028. Baked into these timelines are implicit assumptions that as nimble silicon valley-esque startups they will outpace Chinese state owned enterprises, Chinese construction firms, and Chinese supply chains that are already building, operating and iterating reactors at a dizzying pace.

So how are the Chinese versions doing.

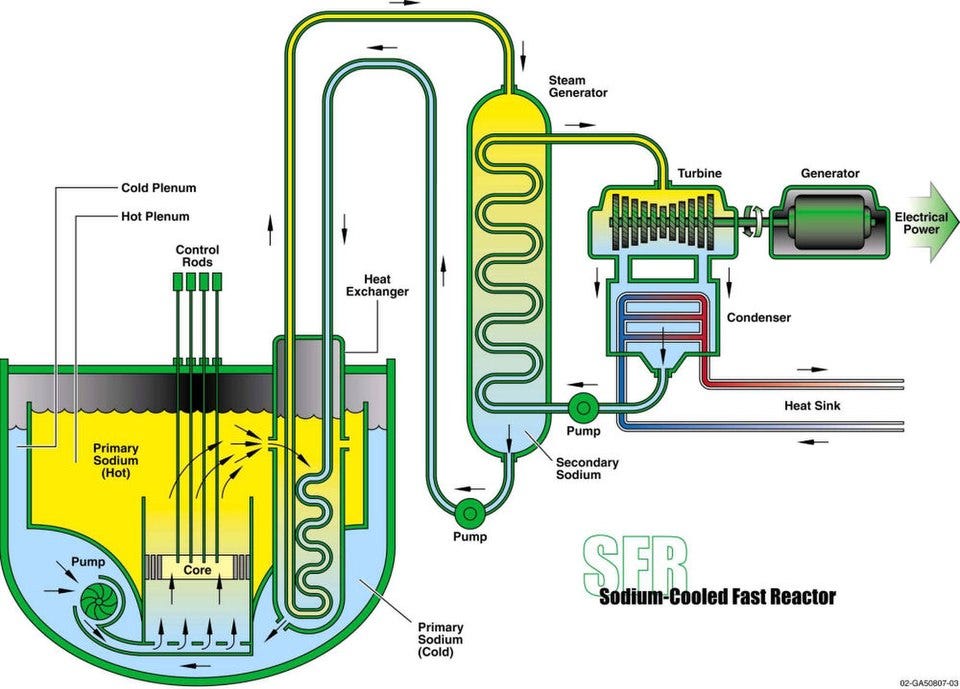

Sodium Fast Reactor

China’s fast reactor program started with a small experimental sodium cooled fast reactor near Beijing. It took 11 years from start of construction to grid connection and a further 3 years to hit a full power run.

The next step is the CFR-600 class. One CFR-600 unit at Xiapu, across the strait from Taiwan, has begun operation after six years of construction. A twin unit is nearing completion. The plan after that is a larger CFR-1000.

Fuel is still coming from Russia. Moscow is supplying high assay, low enriched uranium fuel (roughly 20 percent enrichment in uranium 235) for these CFR-600 units. China intends to localize that fuel cycle eventually, and to close it with MOX fuel from reprocessed material, but for now it is an importer.

Bottom line: China can build sodium fast reactors, but they are not yet a solved commercial product. They rely on significant Russian cooperation and fuel, and there is no evidence they plan on rolling them out by the dozens in the near future.

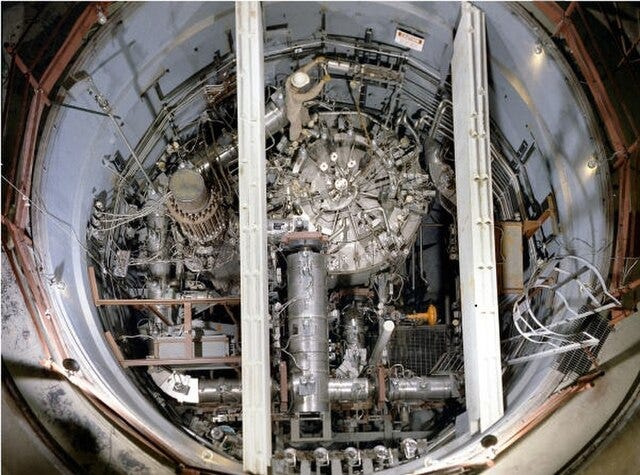

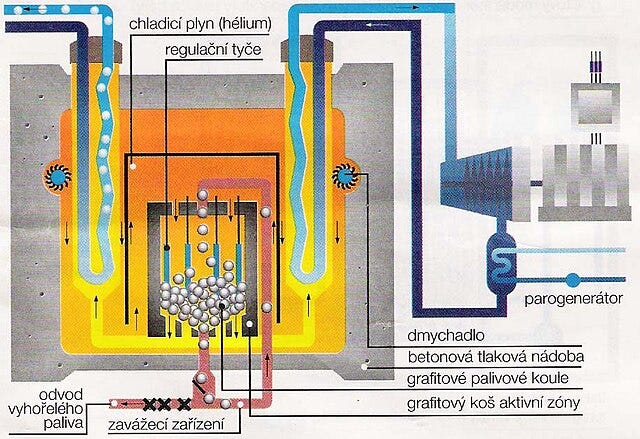

High Temperature Gas Reactor (HTGR)

This is the most hyped category in the West right now in part because of the promise of high temperature process heat for industry. Think X-energy marketing to Amazon data centers and Dows petrochemical plants.

China has actually built two.

At Shidao Bay, China connected a pebble bed, high temperature, helium cooled reactor pair often described as HTR-PM. Each core is on the order of 200 megawatts thermal and they run a shared turbine. This is the world’s only grid connected commercial scale pebble bed high temperature gas reactor.

Here is the reality.

Capacity factor so far is poor. Public IAEA Power Reactor Information System data shows that in its second year of operation it operated on the order of twenty percent availability. This is not baseload level performance.

Online refueling is harder than the brochure implies. Fuel comes in billiard ball sized pebbles filled with TRISO particles. The reactor constantly circulates these pebbles. Burned pebbles are supposed to be discharged, measured for burnup, and either sent for storage or dropped back in for another pass. In practice, the burnup measurement is imperfect. Sometimes partially spent pebbles are pulled out too early. Sometimes pebbles that should be discharged get recycled again. That hurts performance.

Economics look challenging. The next step in the Chinese plan is not a simple repeat build. It is a six pack module, sometimes called HTR-600, where six reactor vessels feed one turbine. That multiplies civil works and fuel handling complexity. François estimates per kilowatt cost could run roughly twenty percent higher than a standard Hualong even before considering the waste liability.

Why build it then. Partly national capability. Partly the idea of pairing high temperature steam with a conventional light water reactor.

China is planning on co-siting one HTR-600 with two Hualong units at a giant petrochemical complex in Lianyungang. The idea is to blend very high temperature superheated steam from the gas reactor with the high volume steam of the Hualongs to supply both electricity and process heat to one of the largest petrochemical hubs in the world by the early 2030s. While it will be a significant project it will be a relatively small part of the overall process heat pie.

ACP100 Small Modular Reactor

In Western marketing, SMR means speed, simplicity, and replicability. Build a small integral pressurized water reactor in a factory and drop it wherever you like.

China is building the ACP100, also called Linglong One, on Hainan Island. It is a roughly 125 megawatt electric integral PWR. François visited the site in August.

His verdict: it is smaller than a full size Hualong, but it is still big. You do not stand in front of it and think “this is a little modular unit I could barge into a mine.” You think “this is still a full civil works megaproject that needs a crane fleet.” The first of a kind unit is taking something like five years to build, which is roughly the same construction time as China’s most recent CAP-1400 reactor build. The project team is already talking about a Version 2.0 that shrinks the balance of plant and tightens the footprint. That is sensible, but it is still in the future.

There is also talk of marine variants, ACP100S and ACP50S, for barges and possibly for ice class or polar service. Here the Chinese face a tradeoff the Russians do not face. Russia fuels its nuclear icebreakers with high assay fuel that lets them run a long time between refuelings. China has said publicly they want to stick with roughly 4 to 5 percent enrichment for export and naval style civilian applications. That means more frequent refueling or shorter range. In other words, even the “floating SMR” story has constraints.

Molten Salt Reactor

China is also pursuing a thorium fueled molten salt reactor in the interior. This is the poster child for “limitless clean energy from thorium” videos that rack up millions of views online.

François’ description is sober. The current machine is tiny, essentially a research scale test bed. The long term plan is to scale, but there is no commercial timeline in sight. The appeal is obvious: very high temperature output, no high pressure water loop. The headaches are also obvious: intensely radioactive liquid fuel, extreme materials and corrosion challenges, and brutally hard maintenance because every valve and pipe becomes a high dose area. If you listened to our recent molten salt deep dive, none of that will surprise you.

Takeaways

China will pass the United States in total nuclear capacity around 2030 without breaking a sweat, yet nuclear will still only be a single digit slice of Chinese electricity.

Natural gas may be a significant future workhorse for new flexible demand like EV charging fleets and AI data centers.

Inland nuclear is blocked less by thermodynamics and more by political memory of floods and by post Fukushima optics.

Advanced reactors are real projects in China, not just slide decks. However their performance is so far underwhelming. Poor capacity factors, in some cases large waste streams, imported fuel, and long construction schedules are the norm.

Anyone in the West who says their sodium fast reactor, pebble bed gas reactor or molten salt reactor will be online, licensed, and selling power in the next two to three years is promising to beat a very competent Chinese state industry at its own game on the first try. That should give investors pause.

Support Decouple

If you find Decouple a useful part of your information diet, please consider supporting us through a Substack pledge or a tax deductible donation via our fiscal sponsor. Your support lets us travel to sites, talk to the engineers who actually build these things, and bring you reporting that goes beyond the press release.