This week, we talk weapons. Professor Alex Wellerstein returns from the set of WIRED (watch his excellent appearance here) to help me understand the origins of Middle Eastern nuclear bomb programs and where they stand today. From France’s covert assistance to Israel’s bomb program in the 1960s to the recent strikes on Iran’s enrichment facilities, Wellerstein shows how nuclear weapons spread through unofficial networks of scientists, spies, and opportunistic allies, and how attempts to stop their proliferation can range from ineffectual to outright contradictory. We explore Iran’s strategic nuclear hedging, Israel’s policy of deliberate ambiguity, and the disturbing possibility that recent attacks on Iran’s uranium enrichment facilities may force the country’s hand toward weaponization.

Watch now on YouTube.

We Talk About

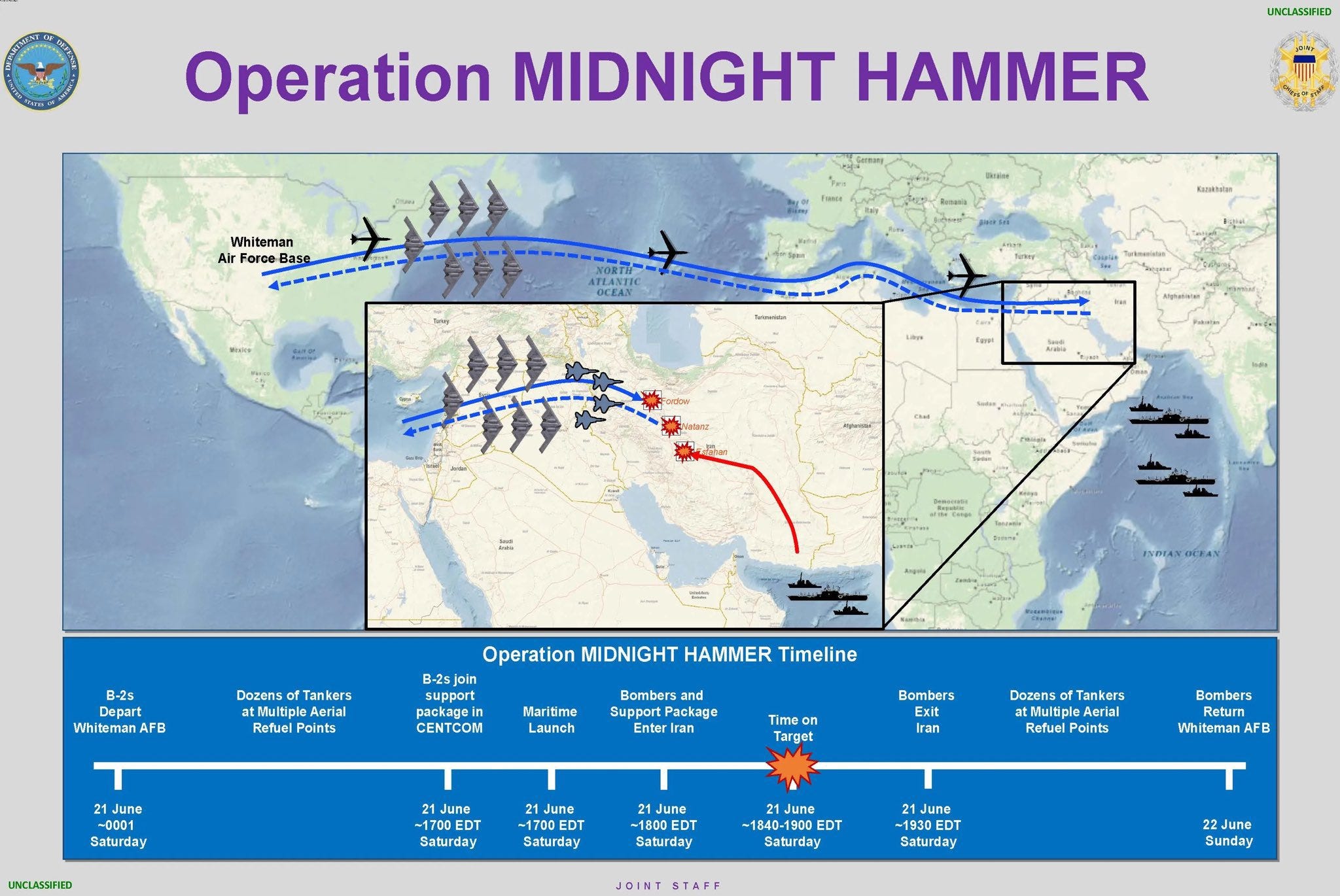

Impact and effectiveness of recent Israeli-US strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities

Iran’s uranium stockpile and the technical requirements for nuclear breakout

Israel’s covert nuclear program and French assistance in the 1950s-60s

The mysterious NUMEC affair and allegations of uranium diversion to Israel

Strategic ambiguity: Israel’s policy of neither confirming nor denying nuclear weapons

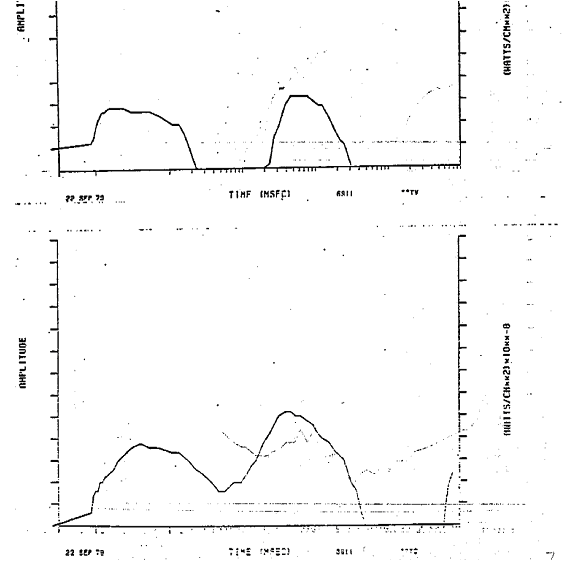

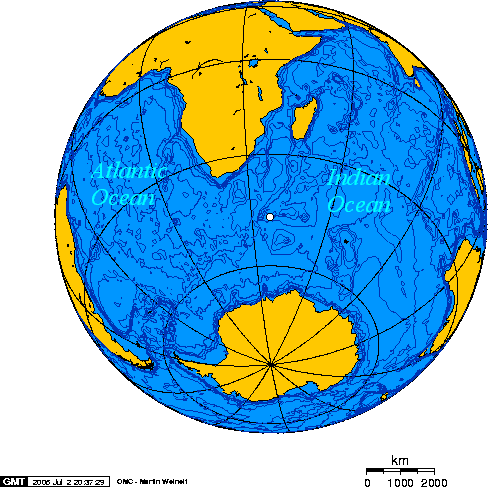

The 1979 Vela incident and possible Israeli-South African nuclear test

Nuclear doctrine in cramped geography: deterrence challenges in the Middle East

A.Q. Khan’s nuclear smuggling network and centrifuge technology transfer

Deeper Dive

“We’re in a period where there’s a tremendous amount of uncertainty. I don’t think the actors involved know what’s going to happen. And that's terrifying.” – Dr. Alex Wellerstein

The recent combined Israeli-American strikes on Iranian nuclear infrastructure were a tactical success but a strategic gamble. The attacks destroyed thousands of centrifuges at Iran’s enrichment facilities, but Iran may have managed to move its substantial stockpile of enriched uranium, the hardest part to replace, before the bombing began. This sets up what Wellerstein describes as a critical decision point: Iran must now choose between diplomatic restraint and a secret race to weaponization. Wellerstein says, on balance, starting the secret race may be the better move for Iran.

Wellerstein helps us understand how nuclear proliferation actually works in practice. Iran’s current position stems from the collapse of the JCPOA, the “Iran nuclear deal,” when America’s withdrawal left Iran calculating that diplomacy offers no reliable security. As Wellerstein puts it, if you’re Iran and you’ve seen what happened to Iraq, Libya, and North Korea, the lesson is clear: “the people who have been in the government there for a long time are very, very willing to use force.” The uranium enrichment from 20% to 60% represents not a weapons program per se, but what Wellerstein calls “hedging of bets.” That is, keeping options open while maximizing diplomatic leverage.

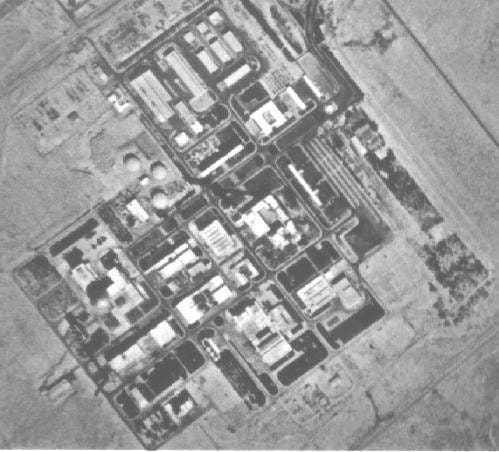

Israel’s nuclear program, for its part, offers a case study in proliferation through unofficial channels. French assistance in the 1950s had a realpolitik justification: France saw value in creating a Middle Eastern “lightning rod” that would draw attention away from its own colonial struggles in Algeria. Israel’s nuclear facility in Dimona, built with French help deep underground, exemplifies the lengths to which proliferating states will go to conceal their activities. When American inspectors arrived in the 1960s to verify claims that this was merely a peaceful research reactor, Israelis had literally bricked up the doors to elevators and stairwells leading to the underground plutonium production areas.

The NUMEC affair reveals the more brazen side of Israel’s nuclear acquisition strategy. Nuclear Materials and Equipment Corporation (NUMEC), based in Apollo, Pennsylvania, served as a middleman for the Atomic Energy Commission, taking highly enriched uranium and reforming it into fuel assemblies for naval reactors and nuclear rocket research. The company was run by Zalman Shapiro, a Manhattan Project veteran, and financed by individuals with deep connections to Israel. Over several years in the 1960s, NUMEC’s “material unaccounted for” reached extraordinary levels: tens of kilograms of 97.7% enriched uranium simply vanished from their books.

The CIA’s suspicions of Israel’s involvement deepened when four men claiming to be Israeli scientists visited NUMEC during a federal investigation. These weren’t researchers but high-ranking intelligence officers from different branches of Israel’s military. They made no serious effort to conceal their identities, meeting openly at Shapiro’s business while he was under investigation for uranium diversion. The circumstantial evidence grew stronger when CIA soil and water samples allegedly taken around Dimona in the late 1960s reportedly showed traces of the same 97.7% enriched uranium that had disappeared from Pennsylvania. As Wellerstein notes, this would be smoking gun evidence… if the reports are accurate. But the documentation remains fragmentary, filtered through multiple accounts, making definitive conclusions impossible.

Israel’s stance on whether it has nuclear weapons has remained one of “nuclear ambiguity.” This doctrine, condoned by the U.S., reflects a calculated trade-off between deterrence and diplomacy. The informal understanding with the United States allows both countries to maintain legal fictions: Israel doesn’t “introduce” weapons to the Middle East, so America can continue military aid without triggering anti-proliferation sanctions. This policy may have prevented nuclear testing, but the 1979 Vela incident—a suspected low-yield nuclear test picked up by American satellites—suggests Israel found other ways to validate its arsenal, possibly through cooperation with South Africa’s apartheid regime.

The geography of the Middle East creates unique challenges for nuclear doctrine. Israel faces the problem of deterring enemies in a region where everyone lives close together. Damascus, Beirut, and Cairo are all within easy striking distance, but so are Israeli population centers. As Wellerstein notes, any nuclear exchange, it is “not the case that they’re going to be dropping 15-megaton surface bursts and irradiating their whole country. That would be stupid.”

Looking forward, the uncertainty surrounding all actors creates what Wellerstein calls a terrifying" situation. The current Israeli government pursues policies whose “end game is not… clear,” while Iran faces pressure to abandon strategic ambiguity in favor of concrete nuclear capabilities. The Trump administration’s unpredictability adds another layer of instability to an already volatile situation.

Technical details about uranium enrichment matter here. Iran’s 60% enriched uranium puts it quite close to weapons-grade material. The separative work needed for each extra percentage of enrichment decreases exponentially as enrichment levels rise. With sophisticated centrifuges, the final sprint from 60% to 90% becomes a matter of months rather than years. This proximity to breakout capability transforms every political decision into a potential nuclear crisis.

Understanding this reality becomes essential as we face a future where more states may conclude that nuclear weapons offer the only reliable guarantee of survival.

Support Decouple

If you find our work valuable to you, consider supporting us by pledging on Substack or making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor at Givebutter.

Note: This written synopsis was produced with the help of modern AI.