This week on Decouple, I sit down with Dan Wang, a research fellow at Stanford’s Hoover History Lab and author of BREAKNECK: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future. We trace how China became an “engineering state” while America turned into a “lawyerly society,” and what that means for infrastructure, energy, industry, birthrates, social security, and human lives. From Guizhou’s skyways to Jane Jacobs’ shadow over North American cities, Wang shows the upside of abundant state capacity and the dark side of excessive control.

Watch now on YouTube.

We talk about

How engineers came to rule in China, and the country that made

The U.S. shift from a builder’s ethos to litigation and regulation after the 1960s

Why Guizhou, a poor province, outshines New York and California on transportation infrastructure

China’s thin social safety net and regressive tax base amid monumentalist infrastructure

State control of capital allocation: the Ant IPO halt, salary caps, and elite precarity

The one-child policy as a moral and strategic failure

Overproduction as strategy: autos, solar, magnets, electronics—scale as leverage

Deeper Dive

“China built its very first highway in the year 1993. 18 years later, it had built one America’s worth of highways. Nine years after that, it’s built another America’s worth of highways.” –Dan Wang

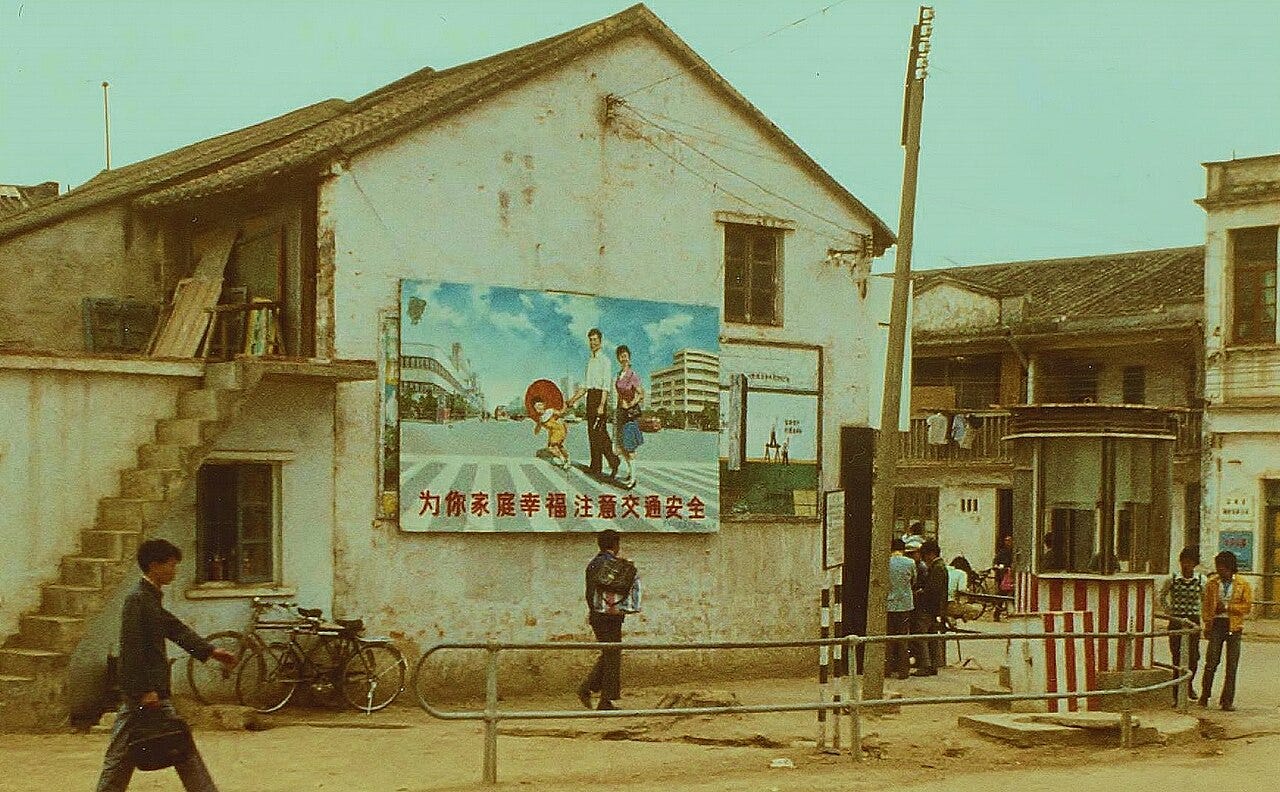

We begin with Wang’s frame: China the engineering state, and America the lawyerly society. The educational backgrounds of leaders in each country reflect this characterization. And the result is plain to see. In China, high-speed rail stitches mountain regions to major markets, airports abound even in poor provinces, and bridges seem to vault across the sky. By contrast, Wang argues, the U.S., stocked with attorneys from Capitol Hill down, has spent a generation teaching law students how to litigate, regulate, and obstruct industrial ventures.

It wasn’t always this way. Wang says Mao, a “man of letters,” introduced “rule by poet.” Famine and the Cultural Revolution proved how costly this could be. Deng reversed course, and China entered its building century. Meanwhile, America, once a “proto-engineering state,” had already laid canals, built rails, raised skyscrapers, split atoms for commercial power, and drawn interstate highways. According to Wang, the 1960s and ’70s changed the moral weather. Figures like Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, and Ralph Nader taught the public to distrust grand projects and the men who ran them. Lawyers became less creative dealmakers and more litigators and regulators. Some of that was overdue, but Wang laments American legal education’s continued focus, in his view, on litigating the problems of past generations when we should be solving for the future.

Yet beneath its monumental infrastructure, China still lags behind the West in many ways: elder care, unemployment insurance, etc. With no broad property tax and heavy reliance on consumption taxes, the system can feel regressive.

The line between engineering nature and engineering people is where the story turns dark. The one-child policy was framed by a missile engineer steeped in cybernetics and overpopulation math. Wang notes that only in a technocracy could a rocket expert guide state population policy. The numbers Wang cites are chilling: peak years with tens of millions of abortions; mass sterilisations; fines, threats, and “persuasion groups”; livestock seized to exert pressure, children blocked from school, and more. Wang says the one-child policy was simply a bad idea from the start. When it began, fertility rates were already falling. When the state pivoted to a three-child policy in 2015, it had to overcome massive institutional entrenchment of the one-child policy in places like the Family Planning Commission, which had over 200,000 full-time employees.

While the poorest may feel insecure in China, so too, Wang says, do the rich. China recently capped senior executive pay in financial institutions, and the state has a heavy hand in tech sector businesses. In America, wealth buys insulation and political influence; in China, fortunes appear to stand on shifting sand.

We zoom out at the end of our conversation. As a grand strategy, China has been overbuilding supply relative to its own demand. It can make two-thirds of global annual car demand by itself and dominates key inputs like rare earths. But while the engineering state is built to produce, it can prove weaker in finance, diplomacy, and culture. America’s lawyerly society is the mirror. If each side leans only on its gifts, both will lose. Perhaps our task is to relearn how to build without casting aside rights and social safety, and to protect rights without smothering action.

Watch the full interview now.

Support Decouple

If you find our work valuable, consider supporting Decouple Media on Substack with a pledge, or make a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor.