“In a sense, you could say Cupertino had the skill, China had the scale, and it was that marriage that [not only] created Apple but… created China.” – Patrick McGee

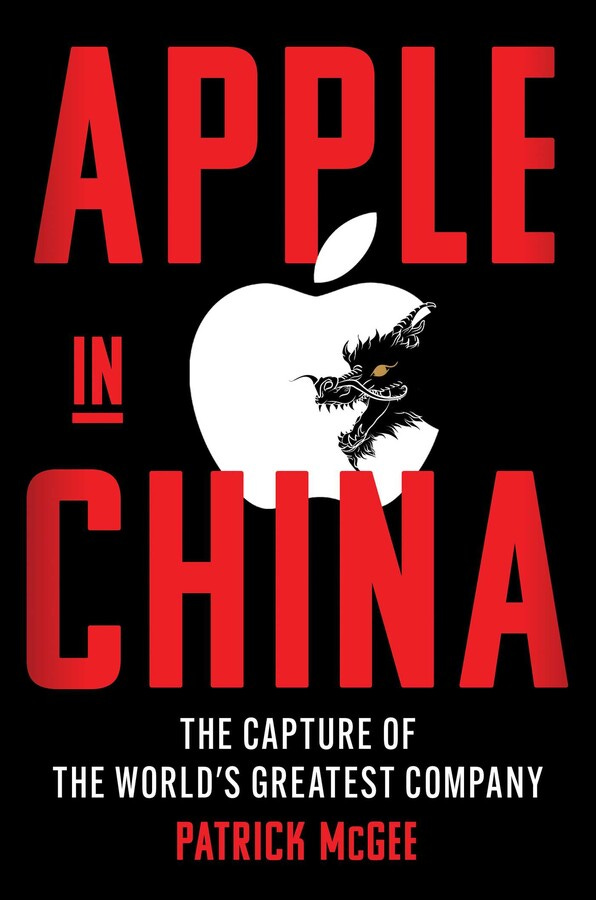

This week, I’m joined by Patrick McGee, a journalist and author of Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company. I recommended this book on LinkedIn as a MUST READ, and stand by it.

Apple in China is an in-depth corporate history which examines one of the most important symbioses in economic history. It explains Apple's meteoric rise in market capitalization/revenue, as well as China's newfound dominance in precision manufacturing. McGee argues convincingly that neither outcome would have happened without this relationship.

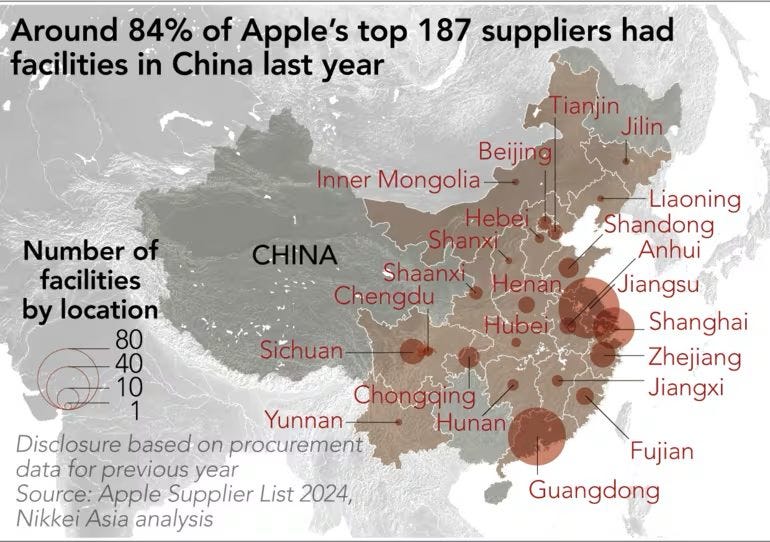

To back up this extraordinary claim, McGee closely maps how Apple systematically sent top engineers from around the world to train up hundreds of factories in China, pressed for demanding specifications at “ridiculously high yield,” and invested sums directly into China that made the post-WW2 Marshall Plan look small. The result? China now leads in 57 of 64 critical technologies, as measured by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, dominating everything from smartphones to electric vehicles.

As Trump threatens iPhone-specific tariffs and Tim Cook promises impossible reshoring timelines, Apple finds itself captured by the very system it helped create. Having accidentally armed its greatest competitor, there is no clear pathway for the U.S. to regain the lead it helped China take.

Watch the interview now on YouTube.

We Talk About

Apple's deep entanglement with Chinese manufacturing

How Apple's obsessive product quality accelerated Chinese industrial capacity

The detailed workings of Apple's Chinese factories

The floating labor population fueling Chinese factories

Apple's massive financial commitments to China

The transfer of global technology know-how through Apple

The political ramifications of Apple's manufacturing choices

Challenges of reshoring high-tech manufacturing to the U.S.

The geopolitical consequences of Apple's China strategy

Deeper Dive

The idea that American technological dominance would be a permanent fixture of life in the West has proven itself to be misguided. Indeed, this dominance may have created the conditions for its own decline.

In what McGee calls “the biggest untold story in tech for the last quarter century,” Apple—the Cupertino, California-based computer company—needed scale and low costs, and China had both. What resulted was a technology transfer so vast it has created “a geopolitical event akin to the fall of the Berlin Wall, but played out over 25 years rather than one night.”

The size of Apple’s investment in China is hard to comprehend. Between 2016 and 2021 alone, it invested $275 billion — double the real cost of the Marshall Plan, which propped up the economy of Western Europe after World War II and is often used as the poster-child of massive economic rescue programs. Apple flew so many engineers, fresh from America’s top institutions, directly to Chinese factories that United Airlines created new routes to cities like Chengdu and Hangzhou just to serve Apple's demand for first-class seats.

Despite massive efforts to automate production, the human input remains staggering. McGee describes factory floors “the size of football fields, line after line” where workers performed 9 to 11-second tasks for 12 hours daily. China’s “floating population,” or liudong renkou, powers this machine. This group of over 300 million rural migrants (close to double the size of the entire U.S. workforce) aren’t permitted to put down roots in cities and offer low-cost labor when and where needed. In purely economic terms, its an advantage the West couldn’t replicate if it wanted to.

Chinese factories in the early 2000s often made cheap, low-quality products. Apple pushed them to manufacture demanding products with astoundingly low defect rates, a process which required grit, inventiveness, and business acumen. When Apple wanted a computer inspired by the look of a sunflower, for instance, manufacturers had to corner the market on aerospace-grade metal, competing with vacuum manufacturers and defense contractors.

Once taught, the knowledge stuck. As Apple trained China's suppliers, those same suppliers began serving Chinese competitors. Huawei's founder even called Apple “the teacher”—recognizing that his company's capabilities came from suppliers Apple had trained. The iPhone “never had more than 20% market share globally,” McGee notes. “Nokia had far higher market share. So who killed Nokia? The Chinese competition. And the Chinese competition was in a position to do that because Apple trained all their suppliers.”

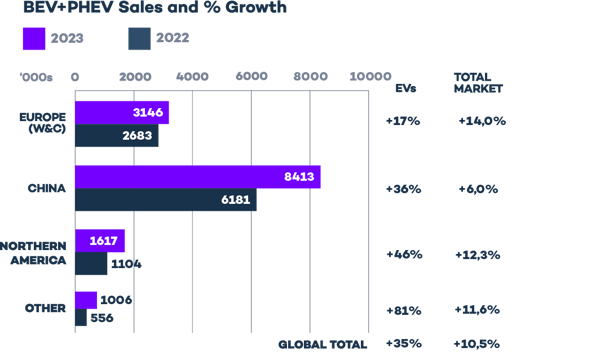

Today, China leads in 57 out of 64 critical technologies tracked by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, up from just 3 out of 64 in the early 2000s. And the gap in technological sophistication appears to be growing. Chinese phones can now unfold twice while iPhones can't unfold once. Electric vehicles, effectively “smartphones on wheels,” dominate global markets using the same supplier ecosystem Apple created.

Apple is now effectively captured by its success in China. As McGee says, “the student has become the master.” When Trump threatened 25% tariffs on iPhones, the company promised $500 billion in American investment—a figure McGee dismisses as “ludicrous.” For McGee, the math only works if you count share buybacks and dividends to American shareholders as “investment,” which is hardly comparable to direct spending in manufacturing capabilities. The trouble with investing in U.S. manufacturing was highlighted by the Texas Mac Pro factory, which was an “unmitigated fiasco” requiring Chinese workers from Foxconn to complete it. “Tim [Cook] hated it,” a source told McGee.

China’s success has raised philosophical questions about capitalism itself. China practices what McGee calls “command and control capitalism” that prioritizes dominance over profits. Their motto: “Without a strong manufacturing industry, there will be no country and no nation.” They deindustrialize competitors by accepting lower margins, subsidized by state support. While American capitalism maximizes shareholder returns, Chinese capitalism maximizes strategic control.

So what is the path forward? Reshoring seems impossible at current technology levels and cost structures. The only realistic path, according to McGee, is “friend-shoring,” building supply chains through allies like Mexico, India, and Southeast Asia. But even that requires accepting that the era of American manufacturing dominance has ended, perhaps forever.

McGee does not offer false optimism. In a way, his book reads like a postmortem of American industrial might, told through the company that embodied Western technological supremacy. Apple created China's manufacturing dominance, then became its prisoner. We taught our greatest competitor everything we knew, then wondered why they knew it better than us.

Support Decouple Media

Apple might be China’s greatest teacher, but on Decouple topics, we hope to be yours. If you find Decouple a valuable addition to your information diet, consider pledging a contribution on Substack or making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor.

Keywords

Apple, China, manufacturing, supply chain, technology transfer, iPhone, Foxconn, reshoring, industrial policy, Xi Jinping, Tim Cook, trade war, tariffs, floating population, friend-shoring