This week, award-winning science writer Peter Brannen returns to Decouple to explore the 4.5 billion-year story of carbon dioxide on Earth. Grounding our discussion is his new book, The Story of CO2 Is The Story of Everything. From the alien world of the Hadean eon to humanity's emergence as the "pyromaniac ape," Brannen reveals how this trace gas has shaped every aspect of our planet's evolution, through Snowball Earth, mass extinctions, and the rise of complex life, culminating in humanity's unprecedented ability to burn fossil fuels.

Watch now on YouTube.

We Talk About

The origin of life and early carbon chemistry

Why Earth needed fossil fuels to create an oxygen-rich atmosphere

The Great Unconformity and Snowball Earth's role in building the rock record

The Carboniferous period as the age of giant insects and coal formation

The Permian mass extinction and Siberian Traps volcanism

The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum as a climate analog

The ice age world that shaped human evolution and the rise of agriculture

How megafauna extinctions marked the beginning of human planetary impact

Deeper Dive

Today, we travel back into deep geological time, exploring how carbon dioxide has been the primary driver of Earth's climate across 4.5 billion years. Our guide, Peter, describes how life here originated at hot underwater vents where geological processes naturally reduced CO2 with hydrogen, creating the chemical foundation for metabolism. We then zoom through “boring billion” years of Earth history, which featured photosynthesis but remained stubbornly low in oxygen because organic matter was consumed as quickly as it was created.

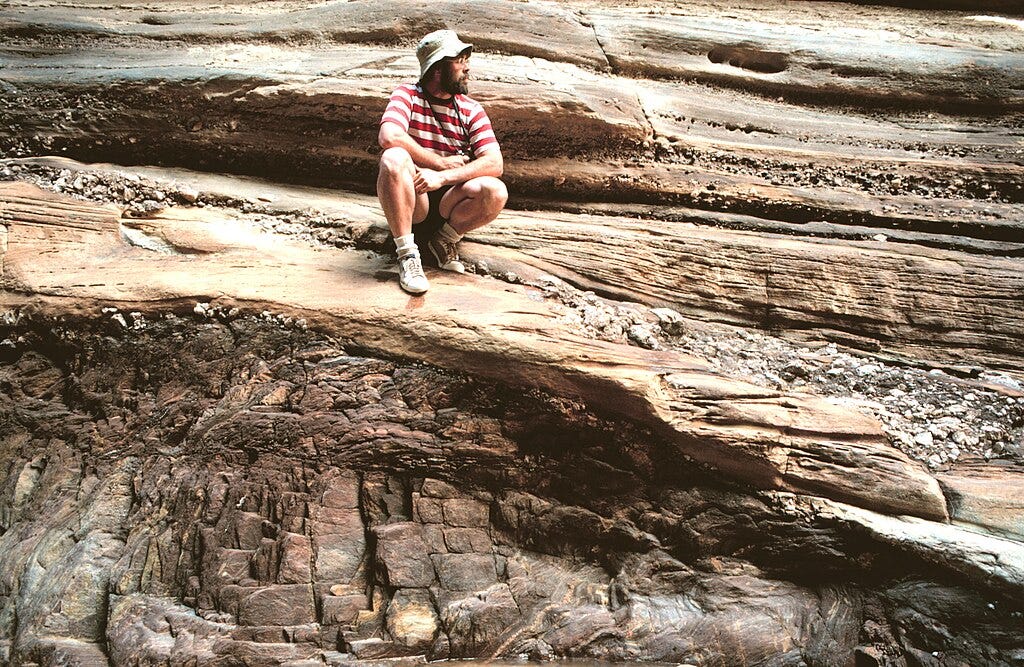

We finally arrive at a great oxygenation event — not the commonly understood one from 2.5 billion years ago, but a later event tied to massive geological disruption. Brannen explores the hypothesis that “Snowball Earth” created what John Wesley Powell, once director of the U.S. Geological Survey, called the “Great Uncomformity.” It could have done this by scraping kilometers of rock off continents, providing the sediments necessary to bury organic carbon. This burial process may be what actually created Earth's oxygen-rich atmosphere: sequestering organic carbon underground interrupted the cycle of decomposition that converts atmospheric oxygen into CO2. The result was more oxygen in the atmosphere. As Brannen puts it, “the reason why you can breathe is because there are fossil fuels under your feet.”

“If I had a time machine, [the Carboniferous] is the place I would least want to go back in all of Earth's history.” – Peter Brannen

At the Carboniferous period, we arrive in a terrifying world of giant insects thriving in a 35% oxygen atmosphere. There are dragonflies the size of seagulls, centipedes as large as alligators, and scorpions as big as dogs. This was the age of coal formation, when 90% of Earth's coal deposits formed in just 2% of its history. The carbon cycle's delicate balance becomes clear when we arrive at mass extinctions like the Permian event, where Siberian Traps volcanism released tens of thousands of gigatons of CO2 by burning through fossil fuel deposits.

We finally come to familiar ground. Brannen frames humanity as an “obligate pyrophile”—a species that couldn’t shun fire if it wanted to—that evolved during the ice ages of the Pleistocene, when CO2 levels dropped to near-photosynthetic chemical limits. Homo sapiens’ “external metabolism,” through fire and tools, allowed us to develop large brains and complex culture, eventually enabling agriculture during the unusually stable Holocene. Although homo sapiens first appeared nearly 300,000 years ago, the true beginning of the Anthropocene may have been just tens of thousands of years ago, when the ice age megafauna that once populated every continent disappeared precisely as humans arrived.

While Earth has experienced higher CO2 levels in the past, today's biosphere evolved for the ice age world of the last few million years. The challenge today is not just the magnitude of change in the carbon cycle, but the unprecedented speed, forcing ecosystems adapted to one climate regime to rapidly adjust to conditions not seen for tens of millions of years. The consequences for complex life could be severe.

Watch the full interview:

Support Decouple

If you find our work valuable, consider supporting Decouple by pledging on Substack or making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor at Givebutter.

Note: This post was made with the help of modern AI.