A year ago, DeepSeek’s R1 model wiped half a trillion dollars off Nvidia’s market cap in a single trading session. The shock wasn’t just that a Chinese startup had produced a competitive frontier model. It was that they did it with two orders of magnitude less compute than OpenAI or Anthropic, using chips the US had banned from export, while American labs were locked in an arms race to stack more H100s in larger data centers.

For a country anxious about losing ground to China across multiple domains (manufacturing capacity, infrastructure buildout, renewable energy deployment, shipbuilding, high-speed rail), AI and semiconductor dominance represented one of the few remaining areas of clear American advantage. The DeepSeek moment revealed that the gap was narrower than assumed and that export controls weren’t creating the bottleneck Washington expected. The response was calls to tighten restrictions further, accelerate domestic chip production, and win the race to AGI before China closes the distance completely.

That moment also exposed a fundamental divergence in what each side fears and what each side is racing toward.

The United States treats AI as a moonshot toward artificial general intelligence (AGI), a digital deity that will either save or destroy humanity depending on which thought leader you ask. The fear? if we fall behind, China reaches AGI first and the geopolitical order flips permanently.

China treats AI as industrial policy, another layer in a decades-long infrastructure buildout designed to raise state capacity, manufacturing efficiency, and quality of life in roughly that order. The anxiety there runs differently: if they fall behind, they fail to escape the middle income trap and their productivity doesn’t outpace their stalling demography.

Regime stability through AI enhanced State Capacity

Western conceptions of Chinese AI tends to fixate on surveillance and social control. Facial recognition at subway stations, digital tracking during COVID lockdowns, and the social credit system all get heavy play. However, there is a more interesting side to this story.

China is deploying AI to increase state capacity right across the board. That includes making high-speed rail schedules more efficient, optimizing power grid load balancing, the banal streamlining of bureaucratic processes like driver’s license renewals, and integrating AI assistants into government service portals. The goal is to make the machinery of the state run smoother, faster, and more responsive.

This connects to a Confucian-inflected model of governance where legitimacy flows from competence. The Communist Party’s hold on power depends partly on delivering rising living standards and partly on demonstrating that the state apparatus functions well. When the subway is clean and runs on time, when permitting a restaurant doesn’t require six months of Kafkaesque runarounds, when energy blackouts don’t cripple coastal manufacturing hubs, the system earns trust.

Compare that to the American deployment pattern. AI in US government services tends to concentrate in immigration enforcement, predictive policing, and bail risk assessment. The neoliberal state has hollowed out administrative capacity in most other domains, so AI gets bolted onto the parts that still have funding and political will: security, borders, and carceral systems.

The Chinese model is no lightweight on surveillance but the broader strategy is to embed AI in logistics, manufacturing, grid management, and public services in ways that make daily life more convenient and the economy more productive. WeChat handles mobile payments, government IDs, train tickets, and restaurant reservations in one app. That creates a granular economic telemetry the state can access, but it also creates a service layer that millions of people use because it works.

The Soviet Computing Paradox and Why China Avoided It

In the 1950s, Soviet mathematicians and engineers were at the frontier of cybernetics. They had elite talent, advanced theory, and a compelling use case: scientific central planning. If you could network computers across the economy, maybe you could coordinate production without the price signals of a market economy.

It failed because the Soviet system was built on chronic information distortion at every level. Factories routinely falsified output data to meet unrealistic production quotas, while ministries jealously hoarded resources to protect their own bureaucratic turf. As a result, the data flowing up the hierarchy was often meaningless, rendering the decisions flowing back down even more disconnected from reality. Introducing computers into this structure did not resolve the dysfunction, it merely exposed it more clearly.

China faced a similar risk. Before Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, it ran a command economy with central ministries managing entire industrial sectors. But China decentralized. It introduced competition within the state sector, tied official promotions to measurable performance indicators, and let local governments experiment with different policies. The center still sets high-level goals, but mid-level actors figure out how to hit them and get rewarded or punished based on efficiency and results.

This is why AI integration works differently in China than perhaps it would have in the USSR. The system isn’t trying to centrally plan every transaction. It’s using AI to optimize specific functions (train scheduling, power dispatch, logistics routing) within a framework where local officials and state-owned enterprises have strong incentives to actually improve performance.

How Chinese AI is Regulated

Regulation in China operates through centralized authority and explicit enforcement, whereas the United States still lacks a coherent framework for governing advanced AI systems. Despite years of congressional hearings and public concern, there is no federal licensing regime for large models, no binding technical standards for deployment, and no single regulator with clear jurisdiction over model training.

The Biden administration’s 2023 executive order on AI relied primarily on reporting requirements and interagency coordination and was revoked by Trump in early 2025, while successive efforts in Washington have focused more on limiting state level AI regulation than on constructing a national one. The practical effect has been to leave governance largely in the hands of private companies and courts, creating a diffuse and reactive system that contrasts sharply with the direct state control exercised in China.

China on the other hand requires foundation models above a certain parameter threshold to be registered with the Cyberspace Administration, and compliance operates at several layers. Companies are expected to curate training data in ways that align with state guidance, to conduct internal content reviews during development, and to implement post-training alignment mechanisms that filter sensitive outputs.

The result is not simply an external censorship switch applied at the end, but a structured pipeline in which data selection, fine-tuning, and reinforcement processes are shaped by regulatory expectations. When a model begins to respond to politically sensitive prompts, such as detailed questions about Tiananmen Square, a filtering layer can interrupt the response in real time, reflecting both technical safeguards and anticipatory compliance by firms that understand the political boundaries within which they operate.

Unlike the USA, China has not been afraid to discipline big tech. When Beijing cracked down on high-frequency trading, banned cryptocurrency mining, and shut down the after-school tutoring industry, the logic was consistent. If an economic activity consumes energy and capital without contributing to long-term productivity or social stability, it gets pruned. AI is judged by the same standard. If it makes factories more efficient, trains faster, or government services less frustrating it gets state support. If it just churns through electricity for speculative gains or social media engagement metrics it faces restrictions.

Chinese AI companies know what the government wants and align accordingly, sometimes because they believe in the goals and sometimes because the alternative is getting shut down like Jack Ma’s Ant Financial.

Energy Abundance and the Western Data, Eastern Compute Strategy

While the United States currently benefits from dominance in advanced semiconductor design, China holds a structural advantage in electricity supply. Decades of sustained annual grid expansion, combined with streamlined permitting and centralized siting authority, have produced an energy system capable of adding capacity quickly to expeditiously absorb large new loads. The American grid, by contrast, has stagnated since the 1980s, and new generation or transmission projects frequently encounter regulatory delays, local resistance, and litigation.

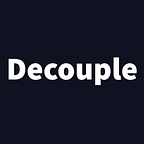

China added more than 500 gigawatts of new power capacity in 2025, roughly 80 percent of it wind and solar with the remainder largely coal. That increment alone approaches 40 percent of total installed US capacity. Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that China could double its already vast grid capacity within five years. This expansion is not driven solely by artificial intelligence. It supports manufacturing, and a deeper electrification project aimed at reducing dependence on oil imports. Data centers, however, fit naturally within that larger trajectory of energy buildout.

The United States faces tighter constraints. Data center proposals often trigger local opposition because they consume significant electricity while creating relatively few long term jobs after construction. Utilities struggle to expand transmission infrastructure at comparable speed. Nuclear additions remain slow and capital intensive. Natural gas projects encounter supply chain and permitting friction. Each of these factors slows the pace at which compute intensive infrastructure can scale.

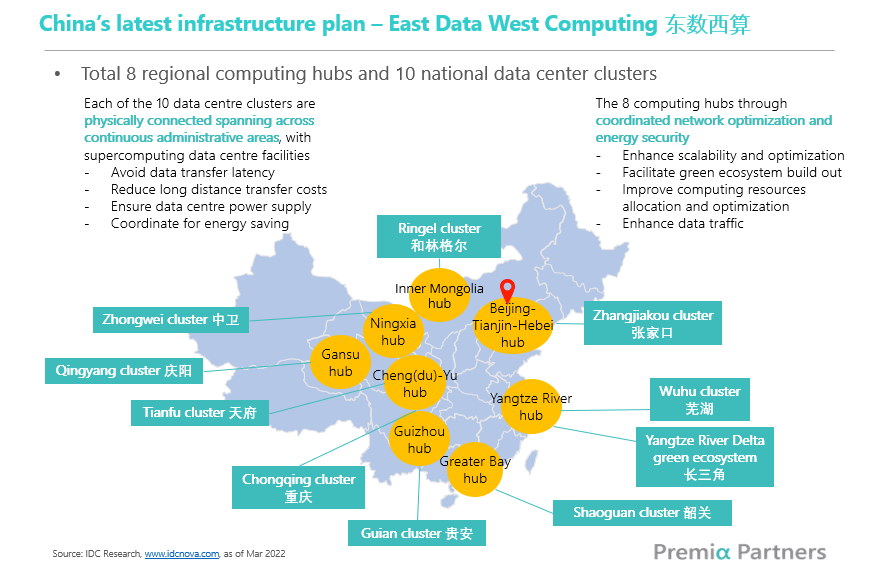

China operates within a coordination structure that allows energy planning and compute deployment to move together. Provincial authorities can designate large data center clusters in interior regions where land, coal, wind, and solar resources are abundant, while national planners align generation and transmission expansion with projected artificial intelligence demand. This approach, commonly described as the Western Data, Eastern Compute strategy, reflects the technical reality that training runs are energy intensive and well suited to bulk coal and renewables power generation in western provinces such as Gansu, Qinghai, and Inner Mongolia, whereas inference workloads are more latency sensitive and therefore remain closer to coastal population centers such as Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Beijing.

Racing in Diverging Directions

The framing of an artificial intelligence race between the United States and China assumes a single finish line and a shared definition of victory. That framing obscures the reality that each country is optimizing for different institutional priorities and deploying artificial intelligence toward different economic and political ends.

The so-called race therefore obscures the real question, which concerns how well each system will translate artificial intelligence into sustained power, legitimacy, and productivity within its own constraints.

Artificial intelligence is molded by the incentives, institutions, and bottlenecks that surround it. The divergence we are witnessing is less about who reaches a singular milestone first and more about how two distinct political economies absorb and direct a general-purpose technology. The outcome will be written not only in benchmark scores or valuation multiples, but in factories, grids, bureaucracies, and the lived experience of economic growth and state power.