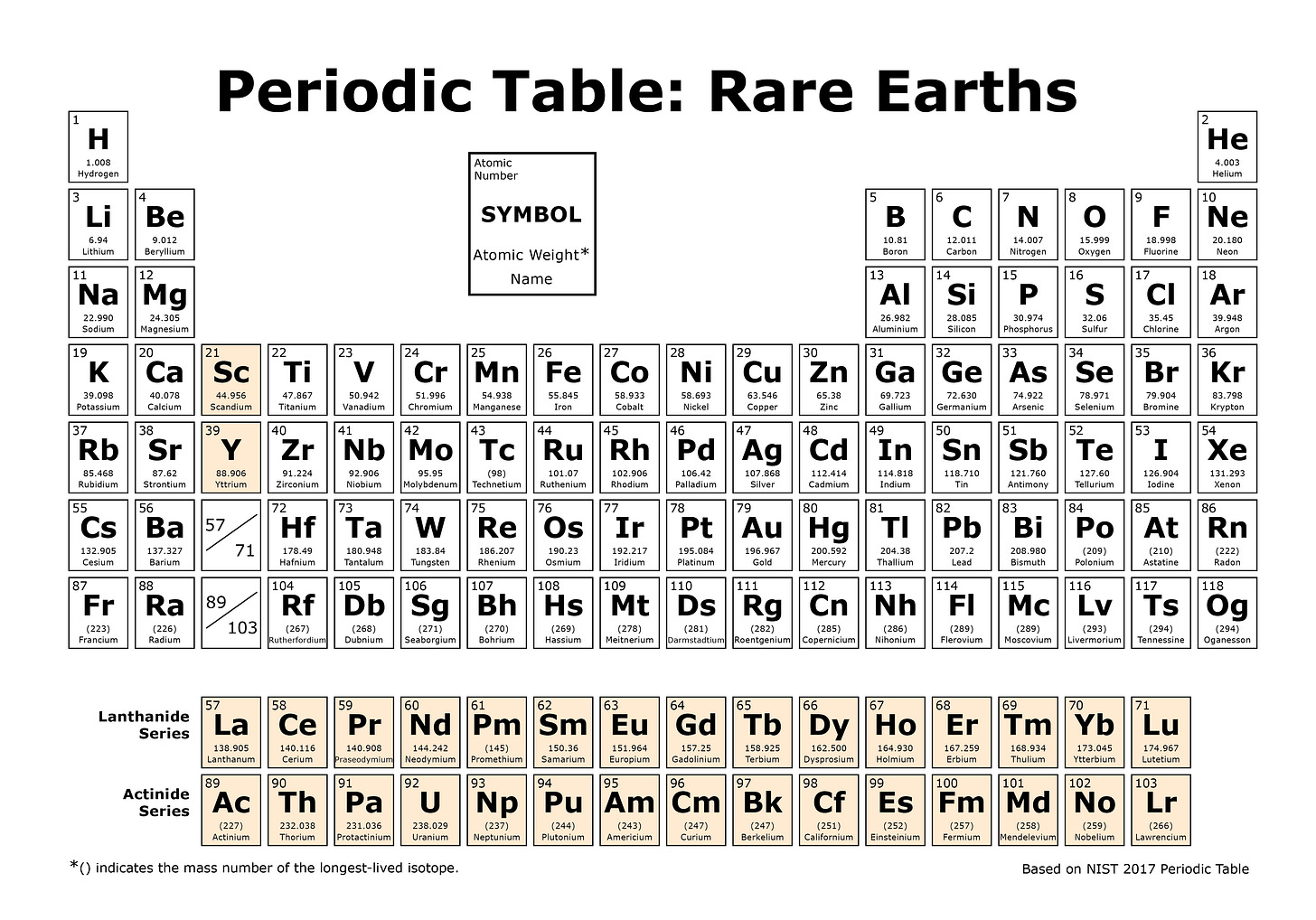

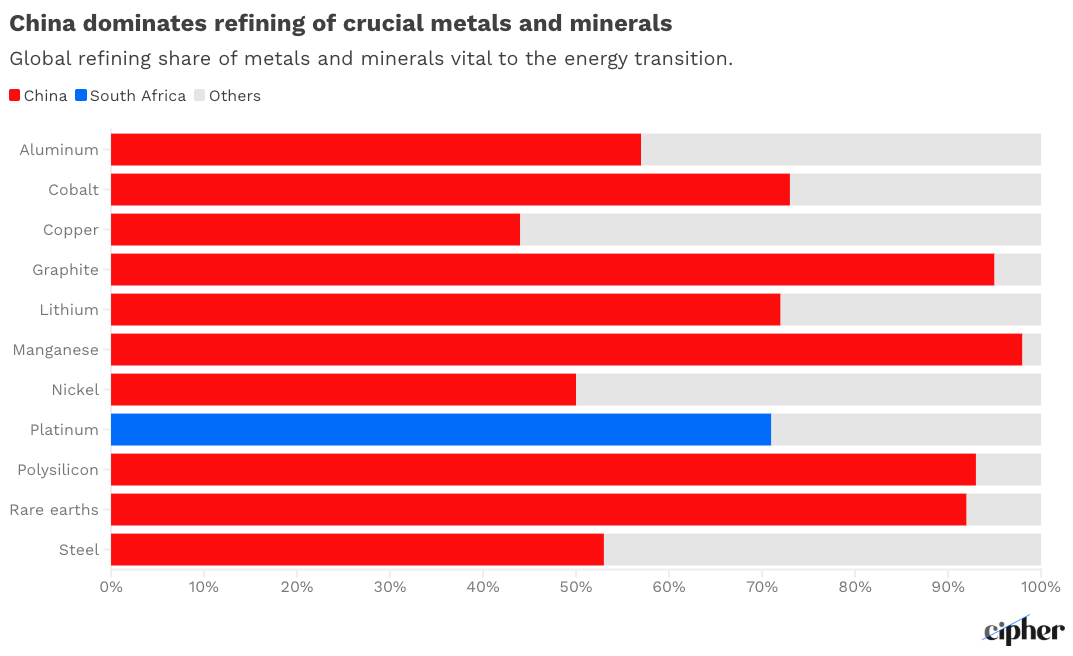

This week, we talk about rare earth metals. What are they, where do they come from, and how are they redefining global power? I’m joined by David Abraham, a natural resource strategist who saw the future of rare earths in 2010 while working in Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. When China cut off rare earth exports over a territorial dispute, Abraham realized these obscure elements, sprinkled into our steel, the magnets in our speakers, the phosphors in our screens, held more geopolitical power than oil ever could. The warnings in his book, “The Elements of Power,” now written 10 years ago, feel like reading a prophecy. Half the periodic table now flows through your iPhone, and China controls 90% of the world's refining capacity for these critical materials. As trade wars escalate and great power competition returns, the country that controls rare earths may control the Earth itself.

Watch now on YouTube.

We Talk About

The 2010 rare earth crisis when China cut off exports to Japan over territorial disputes, and again in 2025

How trace elements and minor metals function as “industrial vitamins” in modern technology

China's systematic capture of the entire rare earth value chain from mining to manufacturing

The complexity of separating chemically similar lanthanide elements through specialized refining processes

Why current U.S. mining operations like Mountain Pass still ship 85% of their output to China for processing

The skills gap between Western coding culture and the hands-on metallurgical expertise China has developed

Historical parallels to World War-era resource competition and strategic stockpiling

The paradox of how Chinese export restrictions actually drove more manufacturing to China

Why focusing on end-use products like EVs could pull supply chains back to the West

The difference between commodity markets and the thin, concentrated markets for critical materials

Deeper Dive

The 2010 rare earth crisis began with a fishing boat near disputed islands in the East China Sea. Japan arrested a Chinese fishing boat captain after it collided with Japanese coastguard vessels near the Senkaku Islands, and China responded by cutting off rare earth exports. In that moment, the world glimpsed the future of resource warfare.

David Abraham witnessed this crisis firsthand while embedded in Japan's trade ministry. What struck him wasn't just China's retaliation, but how few people understood what rare earths even were. These weren't commodities you could see or touch like oil barrels or copper ingots. They were tiny trace elements that made modern life possible in quantities so small they seemed insignificant.

The magic lies in their specificity. Add a dusting of niobium to steel (under precise conditions) and it becomes 30-40% stronger. Embed neodymium in a motor and it can be shrunk to a fraction of its original size while gaining power. These elements don't substitute for each other—cerium polishes glass, dysprosium withstands heat, europium glows red in our screens. Each has unique properties that make certain technologies possible. Without them, fighter jets can't fly, smartphones can't vibrate, and wind turbines can't generate power.

In China, Deng Xiaoping understood this leverage when he declared “The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths.” But his vision went beyond simple resource extraction. While the West celebrated the efficiency of just-in-time manufacturing and outsourced dirty mining operations, China methodically captured each stage of the value chain. First mining, then refining, then component manufacturing, and finally finished products.

The refining process reveals why China's dominance proved so durable. Separating lanthanide elements requires scientists who spend entire careers learning to tease apart chemically identical elements through sequences of acid baths and magnetic separations. This is knowledge gained only through years of handling the materials, understanding their temperaments like a chef knows ingredients.

China invested in this expertise while America forgot it existed. When Abraham attended a rare earth conference in China, he says thousands of scientists filled the halls. A similar conference in Denver drew a few hundred people studying all critical minerals combined. In his view, the scope of human resources dedicated to material science in China dwarfs anything the West maintains.

“We're fighting a battle that we don't have the expertise to win in, yet.” – David S. Abraham

This expertise gap explains why even America's Mountain Pass mine—the sole major rare earth operation in the United States—sold a vast majority of its concentrate to China for processing pre-2025. The raw materials exist in American soil, but the knowledge to refine them resides in Chinese laboratories and factories. Breaking this dependency requires more than capital investment. It demands rebuilding lost industrial capabilities.

The 2010 crisis demonstrated China's willingness to weaponize these dependencies. Paradoxically, Chinese export restrictions drove more companies into China rather than away from it. Japanese manufacturers solved supply problems by moving operations inside China's borders. American companies buying Chinese components avoided export controls entirely. Each crisis tightened China's grip rather than loosening it.

Abraham argues the path forward requires focusing on demand rather than supply. Building rare earth mines without domestic markets recreates the Soviet Union's mistake—producing materials with nowhere to sell them. Instead, Abraham says, America should prioritize manufacturing electric vehicles, advanced batteries, and next-generation electronics. These products would pull supply chains toward domestic markets, creating economic incentives for rebuilding processing capabilities.

The EV represents more than transportation technology. It serves as a crucible for the materials and manufacturing processes that will define future military and civilian technologies. Drone warfare, robotics, and advanced aerospace all depend on the same battery technologies, rare earth magnets, and precision manufacturing that electric vehicles require. Master EV production, and you master the foundation technologies for the next generation of industrial competition.

“There's no Field of Dreams. If we build it, it's not going to necessarily come. We really have to be able to focus on the demand portion rather than the supply portion.” – David S. Abraham

The stakes extend beyond economics. In a world where half the periodic table fits in your pocket, the country that controls material science controls technological progress. China recognized this reality decades ago. The West is only beginning to understand what it has lost, and how difficult it will be to get it back.

Support Decouple

If you find our work valuable to you, consider supporting us by pledging on Substack or making a tax-deductible through our fiscal sponsor at Givebutter.